On Reading the Talmud: Contents and Bibliography

We reach the end, and I have trouble shutting up.

Right, here we are, at the end. Here’s my bibliography, annotated, including both works cited and other works consulted, and some general recommendations.

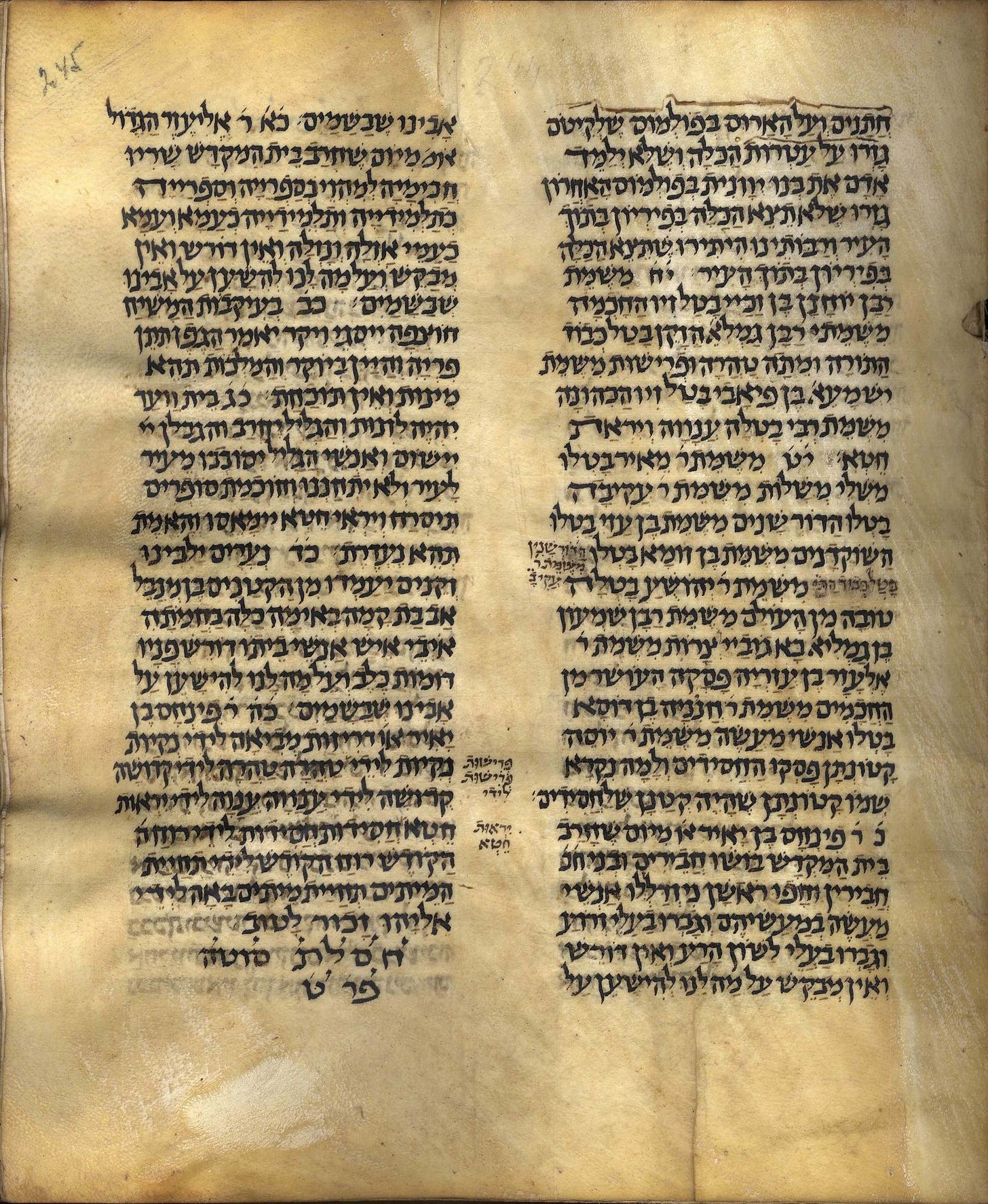

I have also revised and expanded a lot of the footnotes on earlier entries, including, because I’m like that, references to manuscripts, particularly of the Tosefta.

Here is a handy contents for the entire series:

I have, also, in the process of this, read far more of Carrier’s book. Thus the annottation for that title is fairly long, also containing footnotes because I can’t help myself. But that’s important, and contains important observations - albeit many being first impressions. Thus, I will forgo alphabetization for that single entry, and bring that up to the beginning.

UPDATE: Carrier has responded to me. If you come from there, or want to read what I have to say, this is my final word on that, unless he wants to actually, substantially address what I have to say.

Bibliography

Works cited:

Carrier, Richard. On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014.

Our exemplar, of which I have presented much analysis indicating that we may have reason for doubt. At least in some places. In light of Carrier’s longstanding objection to his critics not reading the book, I have read more – though not the whole thing. My impression remains one of deep perplexity. I doubt the connection between the mythic Jesus and the descent of Innana,1 posited partly via equivalence with the “Queen of Heaven” in Jeremiah, more likely a local Levantine deity such as Asherah, of whom I know no similar story-cycle, either as consort of El or Ba’al – despite the assertion that these verses “complain of the prevalence of Inanna-cult among Palestinian Jews” (47) there is no name of the deity presented here, and most consider it at best evidence a local cult, if not solely Deuteronomic propaganda using idolatry as a symbol of infidelity to the Kingdom of Judah. I have never heard of a single biblical scholar asserting that this figure is Inanna. Likewise, Ezekiel 8 is not evidence for anything actually occurring in Jerusalem, but a report of a vision, written in Babylon, probably polemicizing against the unfaithfulness of the Exilic community (as per 3:11, 11:16-25, 39:23-9, etc) thus using a Babylonian cultic figure (Tammuz) as an exemplar. Innana is projected onto the former, the latter is positioned as if it were about Jerusalem, but no evidence of an Innana cult in the Levant is given, nor is a chain of transmission proffered for the centuries between then and the NT (one would expect this to avoid Carrier’s favourite accusation of the possibiliter fallacy). Further, the entire treatment of the Ascension of Isaiah is deeply strange (resemblance is not evidence of dependency), but again I will take one issue as an example. There is brief mention (40) of the norms of the Apocalyptic genre, that “there are copies of all the things on earth, and there the 'rulers of this world' fight over who will control the earth below” but his reading is presented in contradistinction to this, as the religious rhetoric of this genre is effectively because the vision has an earthly counterpart (in much the same way the rhetoric of Ezekiel witnessing things in a vision of Jerusalem condemns his actual targets: the Jews in Exile in Babylon). In this genre a vision of a great beast is significant because it corresponds to a kingdom of violence and oppression down here, and an angel victorious over the beast naturally corresponds to that kingdom’s worldly – not solely celestial – demise. Indeed, it is precisely because of this pattern that we can date Daniel as we do, and that “we” includes Carrier (86). This being the case, why aren’t the same standards applied to a vision that tells that “They wilt lay hands on him and crucify him on a tree, without knowing who he is?” This seems to be the entire point of this part of the text. If not, then presumably it’s plausible that the visions associated with historical events used to date Daniel do not correspond at all and are simply Babylonian visions of demonic entities in the celestial realm. This dating method is also used in the case of 2 Esdras/4 Ezra, widely accepted to be a Christian-edited but originally Roman-Palestinian Jewish Apocalypse, strangely only mentioned in passing (88), even though it is, in fact, a 2nd Century, pre-Rabbinic attestation of a dying Messiah.2 This becomes particularly difficult if one is arguing for this as the source of the concretization of a hoped-for eschatological future – on what basis is the vision accepted as confirmation that what has been promised has actually come to pass? this is a bigger hurdle than it looks: is there any other example of a sect developing thinking such a salvific moment has already come, but solely in the heavens? The entire idea of a celestial soteriological figure appears predicated on the heavens being a kind of waiting room, prior to that being’s hoped-for descent to do the actual salvific work – as per the description given by Daniel, 4QMelchizedek, The War Scroll, etc; and which is recast in later Rabbinic literature, and medieval texts like Zohar.

It also seems notable to me that other examples we have of a sect spawning from the believers of a dead-but-still-believed-in Messiahs were, actually, based on historical people – the primary ones being Shabbtai Tzvi (and his purported reincarnation, Jacob Frank), the late Lubavitcher Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson, and, depending on who you ask, Rebbe Nachman of Breslov.3 I wonder if they would change the probability calculus. Or even consideration of the Baal Shem Tov, who, within less than a century after his death, had one of the largest bodies of miracle stories circulating about him that I know of, including divine ascent, battling evil in the celestial realm, and a spiritualized martyrdom story.

The three primary problems are that:

beyond premise 3 none of the minimal myth model is particularly disputable, and in fact is broadly compatible with Orthodox Christian doctrine and thus prima facie not incompatible with historicism (for them, Jesus was a celestial deity, communicating via prophecy, his stories are allegorical, and some (non-canonical ones) solely so - while others are both allegorical and true, collapsing pts 4 & 5 - to get from this to orthdoxy all you need to do is remove the qalifiers), and

the basis for asserting premise 3 if fraught, as per above, and

in all honesty, much of the book bears uncanny similarity to reading the textual record like a Christian theologian (including occasionally a heady dose of literalism).

It is notable he cites a significant number of Christian theologians for his exegesis of the texts and has continued to do so on his blog.4 That Christian theologians would affirm many of the central points of the minimal myth model, when only one of those points markedly deviates from Christian Orthodoxy should not be surprising. It is an open question whether their opinions should have any bearing on the analysis of the history of the first century environment. This I think the one of the primary causes of two phenomena observable in the reception of Carrier’s work: first, the strongly negative assessment by mainstream scholarship,5 and second, the popularity of his work with former Christians, particularly Ex-vangelicals, who are naturally going to be more used to that mode of thought.6 This is particularly the case regarding Carrier’s interpretation of Messianic prophecy, which anyone familiar with the development of this highly diverse ideology, and who reads the texts in question in Hebrew will find inscrutable, but which (at least to my admittedly cursory familiarity) reads very much like Evangelical Christian literalism.7 His reading of Paul also relies on an incredibly Christian (or, more particularly, evangelical protestant) understanding of Torah, and what its function is, that is not reflected in Ancient Jewish texts – it is entirely conditioned by later interpretations of Paul, who is subsequently a lens through which the entirety of Hebrew scripture is read, which is the foundational Hermeneutic of Christian theology. This is particularly questionable given that Jewish belief on this question is assumed univocal, despite the previous assertion that “when Christianity began … there was no ‘normative’ set of Jewish beliefs”.8 The characterization of early Judaism presented in Elements 1-10 and that presented in his close readings of the New Testament literature are in marked tension with one another. Logical issues also arise: Matthew is cited as a product of the Jewish-Christian movement Paul polemicises against in Galatians (146), but yet inadmissible as evidence because it is tainted by dependence on Paul (266-7; 456-8).9 His analysis of the NT reads like a reconstruction of a combination of Patristic theology, Lutheran Pauline scholarship, and liberal Protestantism, and jumps jarringly from one to the other, and at times completely ignores the scholarly consensus on textual history and provenance.10

In the interests of brevity I will not say more on this but one point: the over-reliance on Christian scholarship, including NT readings (particularly of Paul) explicitly by Theologians, warps his treatment of non-Christian material to a both remarkable and worrying degree. That at times what he offers, in spite of his marked hostility to Christianity, resembles the old Adversus Ioudaios canard that the reality (if not the truth) of explicitly, fully developed Christian doctrine is already so present in pre-Christian Jewish Scripture as to be obvious to even the disinterested observer: basically the same Charge as levelled by Justin Martyr against Trypho and Origen against Celsus’ Jew – is both a fascinating phenomenon, and a concerning one.11

Thus I am highly wary of the probability calculus employed: I expect with more rigorous, less freighted and often partisan analysis, and more comprehensive data, or even simply different categorical distinctions (“messianic figure” vs “saviour deity”; the problematic “dying-and-rising-god” category) the results would be markedly different. Analytic paradigms are only useful insofar as they produce workable results: they are tools, not real types. I am also perplexed by the structure of the book, the final calculation rests almost entirely upon rapid mythologization (see above re: other messianic movements), so what is the rest of the analysis doing? My suspicion is that it is still there to be rhetorically effective, to sow doubt in a less probabilistic manner (cf. conclusions of each chapter) and thus my questioning of that analysis’ rigor is still necessary.

Aśvaghoṣa, and Yoshito S. Hakeda. The Awakening of Faith : Attributed to Aśvaghoṣha. Translations from the Asian Classics. New York: Columbia University Press, 2006.

This is solely cited because the intro addresses a previous translation by a Welsh Baptist missionary to China, Rev. Timothy Richard, in which the Buddha is assumed to be …. well, Jesus Christ, and the Dharma is the gospel and “the Mahayana is not Buddhism, properly called, but an Asiatic form of the same gospel of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ”. An incredible historical oddity, but noteworthy for the (mis)use of typology or mythic parallels to assert dependency or causal relationship.

Bar-Asher Siegal, Michal. Early Christian Monastic Literature and the Babylonian Talmud. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

———. Jewish-Christian Dialogues on Scripture in Late Antiquity: Heretic Narratives of the Babylonian Talmud. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Both of these are extremely important contributions to the nascent field of analysis of intertextuality in the texts of Judaism and Christianity in the late-antique period. The papers which became many of the chapters are available here: https://bgu.academia.edu/MichalBarAsherSiegal

The Chapter “A fool, you call me?” in particular gives a very useful model for the types of methodological concerns required for reading the Rabbinic literature in dialogue with the NT, and for charting continuity between the two.

Likewise, “He who creates the Wind” is a miniature case study for whether assuming narratives about the Tannaim can be taken as reflecting the period in which they are set, and “Rejoice oh Barren One”, while also highlighting the wonderful character of Beruriah, shows a concerted engagement with Pauline thought and Hellenistic philosophy.

Boyarin, Daniel. Border Lines: The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

See my previous note.

———. Dying for G-d: Martyrdom and the Making of Christianity and Judaism. Figurae. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1999.

———. The Jewish Gospels: The Story of the Jewish Christ. New York: The New Press, 2012.

Boyarin is an excellent scholar, and one of a generation who have done incredible work surveying the intellectual history of Judaism, charting the development and transformation of key concepts from late antiquity into the current era. Another, similar scholar well worth reading, is Shaul Magid, though focusing on later thought. His upcoming book on “Judeao-Pessimism” is awaited with much interest.

Cohen, Shaye. From the Maccabees to the Mishnah. 3rd ed. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2014.

A highly accessible survey textbook on 2nd Temple Judaism, if under-referenced (for the sake of conciseness) and slightly out of date. Still invaluable, particularly for collating primary sources. The final chapters are of particular note for our purposes, charting the development of Rabbinic Judaism out of the 2nd Temple Period, and providing sources for the documentation of the nascent competition between Judaism and Christianity.

Collins, John J. The Scepter and the Star: The Messiahs of the Dead Sea Scrolls and Other Ancient Literature. The Anchor Bible Reference Library. 1st ed. New York: Doubleday, 1995.

A great survey of the development of the various strands of messianism attested in the 2nd Temple period. There’s an updated edition of this but I have not consulted it, it’s expensive and not available as an ebook (at least via my library).

Ehrman, Bart D. The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture : The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Epiphanius. The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis. Book I (Sects 1-46). Translated by Frank Williams. Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies. 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

Goodblatt, David. "The Sanhedrin." In The Jewish Annotated New Testament, edited by Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler. 602-4. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

While this is an essay within one, all three of these Oxford volumes (Jewish Study Bible, Jewish Annotated Apocrypha, and Jewish Annotated NT) are very useful. However, the lack of citation in the essays in the volumes makes checking references difficult, and some demonstrate fairly individual perspectives that deviate from the academic consensus. This one is on a fairly controversial topic, as is the Boyarin one in the same volume – I for one am far from convinced that the vocabulary of 5th Century Targumim is of direct relevance for reading the turn-of-first-century (or perhaps later) Gospel of John. I am also far from alone in this. Good for basic background but I would suggest consulting more literature on any topic before considering it authoritative or representative.

Grabbe, Lester. "Sanhedrin, Sanhedriyyot, or Mere Invention?". Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman period 39, no. 1 (2008): 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1163/156851507X193081.

As per above, it’s always good, after reading one scholar’s argument regarding a historical point, to see what other scholars’ responses are. This one I found particularly illuminating.

Halivni, David Weiss. The Formation of the Babylonian Talmud. Translated by Jeffrey L. Rubenstein. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

The go-to summary of Halivni’s source-critical paradigm for the Bavli, now the dominant scholarly position, albeit with some disagreements regarding details. Rubenstein’s translation notes are also fantastic. It is also the only comprehensive representation of this available to English speakers, as his commentary series and many of his essays on the Talmud are only in Hebrew, as of yet.

This is a systematic outlining of the text-critical perspective I have been utilizing throughout this series: the periodizing including the Stammaim, and the evidence of their work: the omnipresence of late unattributed statements, the construction of the dialogue within the sugyot, including introductory questions and explanations framing amoraic statements, inconsistency in attribution, taking up of explanatory statements as if they were the quoted statements they explain, the presence of contradictions and incomplete copying of sugyot between Tractates, sometimes recording earlier versions, the use of forced explanations and so on.

Halivni, in elaborating this, focuses entirely on the halachic sugyot, and limiting his conclusions to this form, but, as per the Rubinstein edited volume below, this methodology has proved incredibly fruitful in the analysis of Aggadah. We ourselves have seen this in our analysis of the Bavli Sukkah passages.

Henze, Matthias, ed. Hazon Gabriel : New Readings of the Gabriel Revelation, Early Judaism and Its Literature ; No. 29. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011.

Additionally, I have been using this annotated transcription: http://www.jjmjs.org/uploads/1/1/9/0/11908749/elgvin_gabriel_inscription.pdf

Himmelfarb, Martha. Jewish Messiahs in a Christian Empire: A History of the Book of Zerubbabel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2017.

An excellent monograph on this text, to my knowledge the first to be written. The book also handily contains a fantastic annotated translation of the entire document. Her perspective on some issues is though less unforgivingly skeptical than mine, but this does not detract from how illuminating this book is. Himmelfarb is more sympathetic to early attribution of Rabbinic statements, and thus cleaves closer to Mitchell’s interlocutor, Klausner, on the dating of the Josephite Messiah – but whether you accept her position or my more skeptical one, both of us are convinced of a Rabbinic origin of this tradition. I am willing to concede that it may be Amoraic (Boyarin would agree), but neither of us think it is pre-Rabbinic. If my argument fails, hers requires answering.

Justnes, Årstein, and Josephine Munch Rasmussen. "Hazon Gabriel: A Display of Negligence." Article. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 384, no. 1 (2020): 69-76. https://doi.org/10.1086/709464.

Litke, Andrew W. "Following the Frankincense: Reassessing the Sitz Im Leben of Targum Song of Songs." Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 27, no. 4 (2018): 289-313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951820718786197.

Is this Targum Near Eastern, or was it perhaps written in Medieval Italy? I don’t know, but this is a very interesting paper.

Mitchell, David. "Rabbi Dosa and the Rabbis Differ: Messiah Ben Joseph in the Babylonian Talmud." [In English]. Review of Rabbinic Judaism 8, no. 1-2 (01 Jan. 2005 2005): 77-90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/157007005774514016. https://brill.com/view/journals/rrj/8/1-2/article-p77_4.xml.

I have addressed this paper at exhaustive length already. Mitchell has a website,

https://brightmorningstar.org/

There is a section of scholarly articles, but it is also worth looking at the books he has authored to get an idea of where he’s coming from.

Mor, Uri. "Two Case Studies of Linguistic Variation in Mishnaic Hebrew." Journal of Semitic studies 65, no. 1 (2020): 117-36. https://doi.org/10.1093/jss/fgz043.

If one thing is older than anything, it appears to be people making fun of their rivals’ accent. Among much other data, we have this here, between Palestinian, Galilean and Babylonian Rabbis.

O'Neill, J.C. "The Mocking of Bar Kokhba and of Jesus." [In English]. Journal for the Study of Judaism 31, no. 1-4 (01 Jan. 2000 2000): 39-41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/157006300X00035. https://brill.com/view/journals/jsj/31/1-4/article-p39_3.xml.

One of the only papers I’ve found dealing with that first passage in Sanh. Even this cursory treatment finds both that it is post-revolt (not difficult) and signs of polemic (more questionable, but still).

The Oxford Annotated Mishnah : A New Translation of the Mishnah with Introductions and Notes. Edited by Shaye J. D. Cohen, Robert Goldenberg and Hayim Lapin. 3 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022.

This is a welcome contribution to Rabbinic literature in translation, and far better than previous translations. It is, however, uneven. The different translators take different standards in some places, leading to confusion, and the usefulness and comprehensiveness of the commentaries vary markedly between Tractates. This is a valuable resource, but no substitute for consultation of the Hebrew text, MSS, and a vast body of critical literature some of which is untranslated. We’re still in the early days of accessibility of this material.

Primus, Charles. "Benjamin Devries." In The Modern Study of the Mishnah, edited by Jacob Neusner. 242-55. Leiden: Brill, 1973.

Knowing something about the positions of the various scholars you’re citing is always a good thing, and, beyond that, the history of scholarship in the field.

Rubenstein, Jeffrey L., ed. Creation and Composition : The Contribution of the Bavli Redactors (Stammaim) to the Aggada, vol. 114. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2005.

This is an excellent anthology, and the introduction is a great summary of the text-critical issues in dealing with Rabbinic narrative material. Full text is available here.

While I have not yet read the entire anthology, Adeil Schremer and Daniel Boyarin have very pertinent essays broadly regarding the Rabbinic construction of history, and the entire third section covers methodology. Rubenstein’s “Criteria of Stammaic Intervention in Aggadah” is an extremely valuable resource. Note in particular the section on “Reference to material further on in the Sugya” which accords with my analysis of the structure of the messianic discourse in Sanh., and the “Kernel and explanatory, dependent clause” which accords with the structure of the entire elaboration in Suk., including the modification of the initial kernel preserved in the Yerushalmi – both features, in tandem, mirror the dialectical structure elaborating a concluded halachic point. All of these are features Halvini identifies as hallmarks of the Stammaic Sugya.

Schäfer, Peter. Jesus in the Talmud. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007.

A good overview and collation of sources. Not sufficient in itself, but an excellent resource, with solid analysis, even if I may disagree with some conclusions.

Sommer, Benjamin D. "Dating Pentateuchal Texts and the Perils of Pseudo-Historicism." In The Pentateuch: International Perspectives on Current Research, edited by Thomas D Dozman, Konrad Shmid and Baruch J Schwartz. 85-108. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011.

This should absolutely be required reading for every biblical scholar, the earlier in their education the better. Full text here.

Van Voorst, Robert E. Jesus Outside the New Testament : An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Studying the Historical Jesus. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Pub., 2000.

This is broadly similar to the Schäfer, though covering more material and thus less comprehensive in its treatment of the Rabbinic material. I am surprised there isn’t a more comprehensive account of the Tosefta in this volume, but it’s a broad introductory survey, with all the limitations of this.

Wald, Stephen G. "Baraita, Beraitot." In Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik. 3:124-28. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2007.

Latest, updated entry here.

Also consulted, and some general recommendations:

Adler, Yonatan. The Origins of Judaism: An Archaeological-Historical Reappraisal. The Anchor Yale Reference Library. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2022.

This is a fantastic study, and I have a review in the works. Stay tuned (by which I mean subscribe if you want to).

Baumgarten, A.I. The Flourishing of Jewish Sects in the Maccabean Era: An Interpretation. Leiden: Brill, 1997.

Both this, and the above, though dealing with earlier material, have been incredibly useful methodological models.

Boyarin, Daniel. Intertextuality and the Reading of Midrash. Indiana Studies in Biblical Literature. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.

See notes above on Boyarin.

Brettler, Marc Zvi, and Michael A. Fishbane. Minhah Le-Nahum : Biblical and Other Studies Presented to Nahum M. Sarna in Honour of His 70th Birthday. London: Bloomsbury 2009.

In particular the Shamma Friedman essay in this collection is a fantastic insight into the transformation of certain conceptual frameworks in the rabbinic imagination.

Brown, Francis, Edward Robinson, S. R. Driver, Charles A. Briggs, Francis Brown, and Wilhelm Gesenius. Brown, Driver, and Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1902.

This is still the best lexicon for general use for those of us who can’t afford the Brill one (and who can afford anything from Brill, really?)12

Fonrobert, Charlotte Elisheva, and Martin S. Jaffee. The Cambridge Companion to the Talmud and Rabbinic Literature. Cambridge Companions to Religion. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

I am still working my way through this collection. Like all the Cambridge and Oxford Handbooks it’s not so much an introduction as a selection of essays dealing with a variety of modern critical perspectives. The essay on orality is particularly good, as is Boyarin’s on Hellenic thought in Rabbinic Babylonia.

Hauptman, Judith. "Does the Tosefta Precede with Mishnah: Halakhah, Aggada, & Narrative Coherence." Judaism 50, no. 2 (2001): 224-40.

This is a bold and very valuable contribution to rabbinic textual theory. I need to read Hauptman’s monograph on the Mishnah as a result of this, but have yet to do so.

———. Rereading the Rabbis : A Woman's Voice. New York: Routledge, 2019.

———. The Stories They Tell. Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2022.

Both of the above are great examples of reading Aggadah in context, its purpose and the function it plays within the Rabbinic corpora.

Jastrow, Marcus. A Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midraschic Literature. 2 vols. London, New York: Luzac & co.; G. P. Putnam's sons, 1903.

As with the BDB, this is the best widely available and affordable reference lexicon. The Yitzhak Frank is also useful while learning, as it includes abbreviations (always useful), inflections rather than solely roots, and rabbinic idioms, but it comes from a decidedly orthodox religious perspective.

Kahana, William G. Braude, and Israel J. Kapstein. Pĕsiḳta Dĕ-Rab Kahăna. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1975.

This is an old but very serviceable translation. The primary value however is the commentary including numerous cross-references.

Noam, Vered. "Pharisaic Halakha as Emerging from 4qmmt." In The Pharisees, edited by Joseph Sievers and Amy-Jill Levine. 50-65. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2021.

The big take-away from this paper, for our purposes, is the identification of two divergent Tannaitic Halachot of the Red Heifer. The existence of features like this is strong evidence that even the Tannaitic material is composed of multiple layers, and already evidences redactional and revisionist activity, thus necessitating attentiveness in treating this material on a historical level. Very interesting to read alongside Hauptman’s work on this subject, see above.

Rose, Gillian. "Ethics and Halacha." In Judaism and Modernity : Philosophical Essays. 25-32. London: Verso, 1993.

Not directly relevant, but Rose is a favourite, and this essay makes illuminating points about how modern hermeneutics can warp the relation to texts and produce distortions. Speaking primarily on a modern cultural context, but methodologically generalizable. Showing my true colours here as an enjoyer of grumpy Jewish dialecticians, but there you go.

Sanders, E. P., Albert I. Baumgarten, and Alan Mendelson. Jewish and Christian Self-Definition. 1st American ed. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1980. Vols 2 and 3 only.

Again, still to work though these volumes systematically, but there are some very fine essays in here, including Halivni. A bit old, but the field is young. And the history of scholarship is something both important, and of which the importance is often underemphasised. It is interesting to observe the ongoing development of the field, comparing earlier work by the likes of Cohen and Baumgarten to their more recent work, as well as reading Halivni, Shiffman and the other writers covering the Rabbinic literature prior to the critical shift instantiated by Halivni’s Mekorot Umesorot.

Sommer, Benjamin D. Jewish Concepts of Scripture : A Comparative Introduction. New York: New York University Press, 2012.

This is a fantastic anthology of essays covering the differing and transforming attitudes toward scripture, broadly defined, across the arc of Jewish history and thought. A very important read for those who assume that because Jews and Christians share (some of) the same scripture, their attitudes toward it must therefore be similar – or those who think the Bible has always been read in the same way. Sommer’s citation of the distinction between scripture as “formative” and scripture as “normative” is very useful.

Stemberger, Günter, Hermann Leberecht Strack, and Markus N. A. Bockmuehl. Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: T&T Clark, 1996.

This is less an introduction and more a comprehensive textbook/reference volume. As a book initially written in the late 19th century, revised in the 20s, heavily re-worked by the co-author in both the 80s and the 90s, then with another revision to create the 2nd edition of this translation, it has been thoroughly transformed from an introduction into what is more like a scholastic compendium. It does have lists of Rabbis and their generations, dates from the redaction of various texts and other useful data all in one place, which is a plus. However, given its editorial history, the content is also wise to check against other sources. It is fun to ponder the parallels between this transformative revisional textual history and that of its subjects.

Wise, Michael Owen. Language and Literacy in Roman Judaea: A Study of the Bar Kokhba Documents. Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library. Yale University Press, 2015.

This provides both important demographic data on the various levels of literacy in Judaea around the time of the first Revolt, in a tri-lingual environment, and one of the most important pieces of evidence tracing the development of Hebrew dialects in the post-Biblical period, providing a link in the chain from late-Biblical texts, through Qumran, to the Rabbinic period. This study should be of interest particularly to NT scholars (of which I am not) regarding the evidence of Greek literacy in Judaea in particular, and what we can glean from that about education at the time. This data may have bearing on the interpretation of the fact that all the NT documents that survive are in Greek.

Additional note: if there is a Christian parallel to this narrative it appears to be, rather than the canonical Gospels, the Harrowing of Hell, which only emerges (from memory) in the early Medieval period. The parallel to the gospel narrative appears incredibly strained.

7:29, if that verse is not the work of Christian editors, given that idea not appearing in the later messianic vision of Ch. 13 – this is in fact why older Rabbinic scholarship, such as that argued against by Mitchell, dates the origin of the Mashiach ben Yosef to the late 2nd century, attached to the failure of Bar Koseva’s revolt and the messianic hope invested in him.

Arthur Green argues that messianism is present from the beginning of the movement, implicit in the writings of his primary disciple, Reb Nosson, in Green, Arthur. Tormented Master : A Life of Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav. New York: Schocken Books, 1981. I am not necessarily entirely convinced, but at the very least it appears certain he was considered the reincarnation of R’ Yitzchak Luria, and, thus, of Shimon Bar Yochai, and probably also Tzaddik Hador. This does not necessarily entail him being Mashiach, but is also not far off.

e.g. Hugh Anderson, Clinton Arnold, Margaret Barker (a highly controversial figure), FF Bruce, Charles Gieschen, Martin Hengel, Kim Jintae (teaching staff at the Seminary at Liberty University!), Andrew Lincoln, Bernard McGinn, NT Wright; on his blog Daniel Sadananda, Frank Holbrook, Meredith Kline, Carroll Stuhlmueller, J. Cameron Fraser, Barker again, Hengel again, Mitchell who I have already addressed, among others. Citations appear to be selected solely based on whether they can be proffered to back up a point, with little assessment of how that position is arrived at, nor exploration of the consensus position (often not even addressed in passing) and why it is being rejected in favour of a fringe position. That something has passed peer review in a journal of Seventh-Day Adventist or Evangelical Theology has little bearing on its value for historical-critical purposes. This is highly inconsistent with his continual insistence that his critics are crypto-christian apologists.

the repeated citation of theologians primarily interested in Christology and the univocality of the ‘Old Testament’ and the New is never going to be popular with historical scholars.

See in particular the story that Derek Lambert relates of his journey through literalism, calivinsm, full preterism, and eventually into mythicism, before realising the difficulties with all of this.

See in particular regarding 2 Sam. 7:12-14 (576-7), which, in the Hebrew, doesn’t support Carrier’s reading – the word זרע is far broader than this reading requires, and there is no attestation of ancient Jews thinking in these kinds of terms – indeed the tools to move beyond such literalism are supplied in the various conflicting other prophecies that produce the variety of messianic thought that develops (Isa. 11:1 is already a revision of this, as a “stump” is something that has been cut off). This follows for his reading of Paul in the following pages, which reads like an explication of Pauline theology (in the school of NT Wright), including the inclusive “we” used throughout. I would not be surprised if these pages excerpted would be indistinguishable to many from the coursework produced at a protestant seminary.

This assertion as well can be problematized in several ways, not least of which by way of the sea-change in scholarship in this issue by EP Sanders, and the recent contribution to this by Yonatan Adler. A review of his contribution will follow, and, following that will be an extended essay on the development of Halacha in the 2nd Temple context.

If this were the case, what is going on with the also-discussed, pre-Pauline “Torah Observant” Christian movements (146, 281-2, 284-5, described as “from the original sect of Christianity”)? Paul appears an innovative deviationist in this case, and thus evidence of his belief gives us little information about said “original sect” much less what they believed. Given Markan Priority (which I don’t dispute) this also relies on a bizarre assertion that Mark presents a (very Lutheran) Pauline supersessionist-antinomian theology (including taking the Pharisees, rather than as a sect, as representative of the Jews as a whole, 414, and missing the racialised insult aimed at the Syrophonecian woman, this is only dressed up in Matt, already present in Mark, 7:26-7) a reading not supported by the text nor any scholar I know. Mark may be making some use of Paul (or reproducing similar ideas) but his theology at least on this point is Markedly different (pun intended). The purported basis for this includes citing the specific wording of Targum Jonathan on Zecharaiah as the basis for Mark’s temple cleansing narrative, even though the provenance of this Targum is uncertain (and very possibly post-NT), and, further, we do know that it edited heavily at various points and is cited in variants in the Amoraic literature. Relying on a single word in Targum as the source for a Gospel episode is not defensible. Carrier also might want to look into when the Haggadah for Pesach was composed (certainly post-1st Century, cf 426-8). Given what is argued elsewhere, the evidence from Paul seems just as compromised as anything else, and anything extrapolated from that fails to give as an account of origins.

In addition to the above-mentioned treatment of Targum Jonathan, see the treatment of the Epistle of Eugnostos, widely considered (if there even were a pre-Christian original version) to reflect a neopythagorian, not “Jewish Gnostic” origin (indeed the existence of Jewish Gnosticism is highly contested), though later edited by Christian Gnostics. And the aforementioned ascension of Isaiah, of which Carrier is the first I have read to argue for the interpolation of 11:3-21, which appears to remove the entire rhetorical coherency of the vision: as per how apocalypses function, given above – the argument reads like arguing that the stylistic discontinuity between the visions of beasts and the mundane political explanations given by the Angel are evidence of interpolation – and thus extremely forced.

[edit to add: I have now been informed that there is a case to be made for this interpolation, but, crucially, that does not, in any way, directly lead to Carrier’s reading (nor is it conclusive): the vision itself appears predicated on the occurance of the events narrated, either in, or necessarily being linked to, the terrestrial world. I know of no text in which such would not be clearly implied by such a “prophetic” vision. Certainly the entire apocalyptic genre indicates that this would be the expected result of such - and, importantly, as these texts are generally ex eventu, it appears to indicate the author thought that such had already occurred.]

“Dan. 9.24-27 […] is already unmistakably clear in predicting that a messiah will die shortly before the end of the world, when all sins will be forgiven; and Isaiah 53 is unmistakably clear in declaring that all sins will be forgiven by the death of God's servant, whom the Talmud identifies as the messiah” OTHOJ, 77. Emphasis mine. Cf. Rom. 10:16-21; 11:7-10.

Yes, I know the Baumgarten I cited is also Brill, but I found that at my favourite kind of 2nd Hand Bookshop: the kind that don’t check how much something goes for and just eyeball the price.

Hello, have you also read Peter Schäfer's "The Jewish Jesus: How Judaism and Christianity Shaped Each Other"?

I saw it while going to buy his "Jesus in the Talmud" and was wondering if you had read it.