On How to Read, and How Not to Read, the Babylonian Talmud from a Historical-Critical Perspective (I)

An introduction to historical-critical study of the Bavli, part I of many

This is the first part of my very long intro to the historical-critical study of the Bavli (the Babylonian Talmud). The inspiration for this is the somewhat-bizarre treatment of the Bavli by Richard Carrier, using the passages he cites to model contemporary critical methodology, but it has turned into much more than that - and become far longer and more densely cited - than was originally intended, so I decided to create this and post it here. Hopefully this is for the good, and transcends the idea of any kind of simple back-and-forth debate.

This is intended to be introductory, but there is little material on the Bavli that is anywhere close to introductory, and it will get complicated fast. I hope it is as accessible as I intended it to be. Believe it or not this is a fairly basic reading.However, in aid of accessibility I have linked to as many open access resources, lectures, conference papers and the like that I can find and added these to the references. This should also be entirely accessible to people with no experience in Hebrew or Aramaic.

I am serializing this into bite-sized chunks as I doubt many people would want to read 20,000 densely-footnoted words in one go (this first installment is light, but it gets heavier), but if I am wrong on that let me know - I have weird taste, as do many others, but how weird, who can say.

Most of this is already written, and I am just editing it - so the series will be updated fairly regularly.

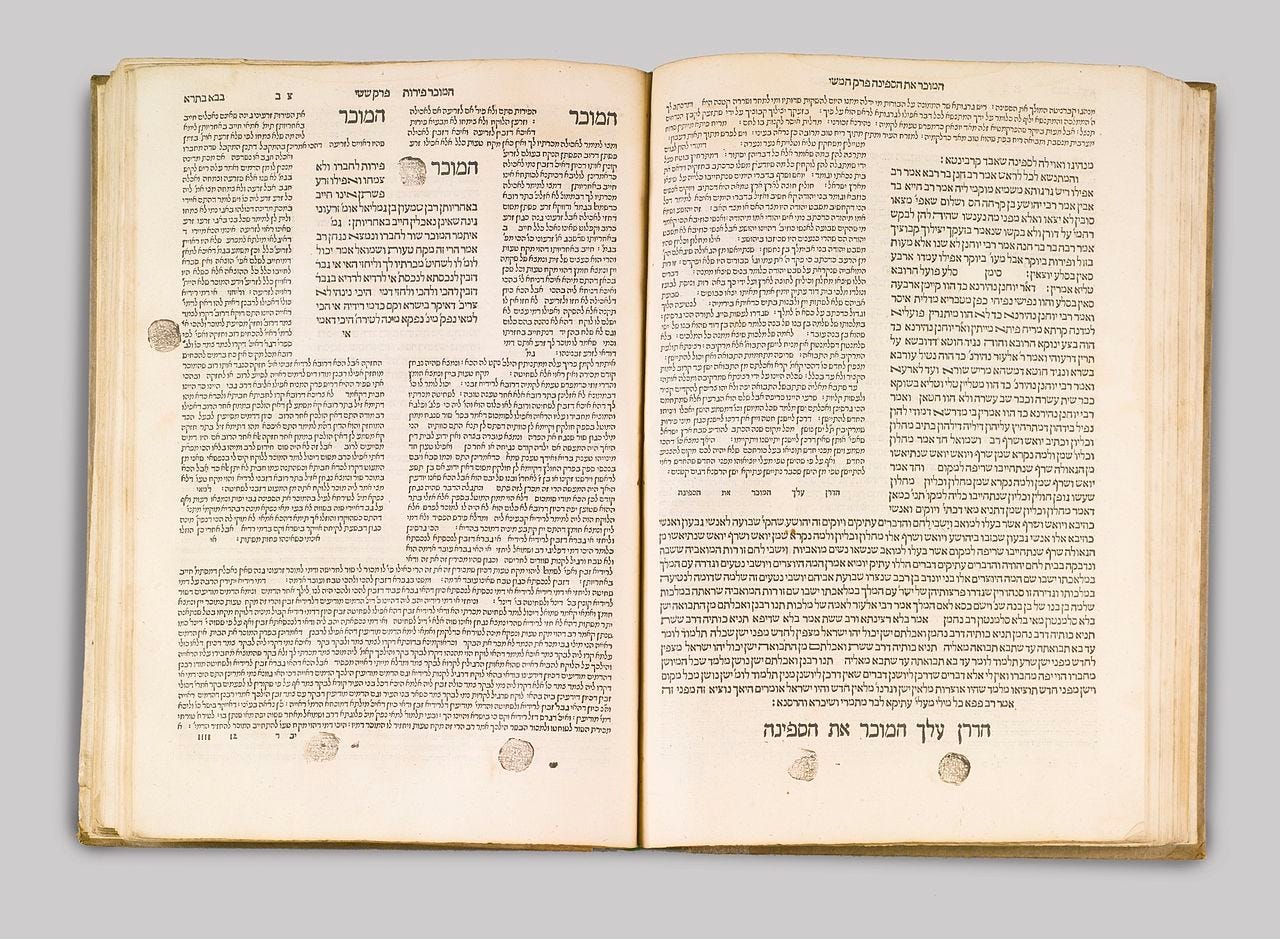

The Babylonian Talmud, or the Bavli, is an enormous and very often misunderstood work, even by those who spend much of their lives between its pages. It consists of 2,711 of large folios, conventionally numbered from the Vilna edition, and, reading a single side of a folio (a large page, around A3 size) a day, those who commit to reading it in its entirety as part of “daf yomi” (a page a day) complete this labour in just under seven and a half years. However modern, critical scholarship of the Bavli is a relatively young field, and much of it takes place in Modern Hebrew (there are no good introductory textbooks in English that I am aware of, the Strack/Stemberger introduction to Talmud and Midrash is somewhat out of date, and not particularly introductory), and thus the nature of the text from a critical standpoint is understood by even fewer than have read much of it.1

But, to start, what is the Babylonian Talmud? To answer that question, we must return to the very beginning of the Rabbinic tradition. Sometime after the sack of Jerusalem in the failure of the rebellion of Bar Koseva (better known by the pseudo-messianic epithet Bar Kokhba, which I will avoid because of those implications), a decision was made by the Rabbis to create a written body of religious writing, focusing mainly on interpretation of Biblical law. This process resulted, sometime following 200CE, in the completion of the Mishnah (though some material, the “minor tractates” and additions to the major ones, were added later, including one we will encounter). The Mishnah is a digest or compendium of opinions and various related writings, organized around a series of six broad categories (orders, sedarim, סדרים) each containing seven to twelve tractates (masechtot, מסכתות), covering more specific matters, such as the Sabbath, each of the festivals, prayer, marriage and so on. Somewhat confusingly, the whole body of work is The Mishnah, but each paragraph within it is called “a Mishnah”, the plural of which is “Mishnayot”.

But the Mishnah in itself was not a completion – no one said, “ok that’s done, that’s all we need”. Firstly, the Mishnah is often reluctant to cite what the biblical basis of the opinion it gives, and secondly, there were other, non-Mishnaic writings produces around the same time, or in the ensuing centuries, first the Tosefta (fragments related to the Mishnah from roughly the same time, or slightly later), and later the various other traditions, including the early Midrashim (singular “Midrash”, biblical commentaries, most originating in the post-Mishnaic period but being added to across centuries, some not completed prior to the rise of Islam) were compiled and completed, and traditions from early generations were passed onto later ones.

For the understanding and application of Biblical Law, this presented a problem for later rabbis. Where in Torah do these specific opinions come from? What about these other texts and compendia? What about this other verse that seems to suggest otherwise? These are the questions answered by the Gemara – the commentaries on the Mishnah, often presenting Tosefta, material from the Midrash and other sayings, collectively called Baraita (plural: Baraitot, roughly meaning “outside material”), interpretative and exegetical material providing relevant biblical quotations, often in the name of rabbis from the Amoraic period (3rd to 5th Centuries) incorporating these together, and adding complex, tangential, argumentative, and at times inscrutable discussions ostensibly based on (but often veering far from) the Mishnayot of each Tractate and each Order. The Yerushalmi – the Jerusalem or Palestinian Talmud – was the first to be completed, (sometime between 400 and 500 CE), and tends to be more terse and perfunctory in its treatments, and the Bavli, the Babylonian Talmud, was completed later, often incorporating and expanding material contained in the Yerushalmi (most general estimates give a date around 600 for the majority of the core content, with additions and editing extending further, perhaps as far as the 8th Century).2 Often what the Bavli Gemara is doing is trying to thread the needle connecting these various disparate parts together and working through implications of said connections. The result is a complex, often confusing network of intertextuality and mutual citation, with opinions providing a voluminous list of authorities, often diverting itself into seemingly unrelated topics, stories, anecdotes and territories which turn out, at least sometimes, to be deeply interwoven.

But, to put it simply, this is how we get Talmud – which, if not otherwise specified, normally refers to the Bavli – and, for both Talmudim, Talmud is Mishnah and Gemara together. When people quote “the Talmud” often what this means is the Gemara, the commentary on the Mishnah either from the land of Israel, or more often, from Babylonia. To compare the scope of this, the Mishna set I have sitting on my bookcase is 3 volumes (with some commentary) and a standard set of Talmud Bavli is around 20 volumes, or more.

However, the way Talmud presents itself is often very different from what it is. On the face of it, and, within its own claims about its nature, it is the Oral Torah, or at least part of it. It represents itself as the record of an unbroken chain of oral transmission, extrapolation and interpretation, from Sinai through the prophets to the “great assembly” at the time of Ezra, and, through the second temple period to the time of its writing. Thus, Rabbinical figures are quoted and quoted, from the time of Ezra and Nehemiah through Hillel and Shammai in the 1st century BCE (called the period of the Zugot, the pairs) through to Rabbi Akiva at the time of Bar Koseva’s revolt, Yehuda Hanasi’s redaction of the Mishnah at the conclusion of the 2nd century ( or early 3rd, this period being the end of the period of the Tannaim), through to the later generations of Rabbis in Palestine and Babylonia in the fifth century (the period of the Amoraim). It looks as if these opinions are simply recorded and passed down (x said in the name of y who said in the name of z, though often two rabbis of different generations will be quoted as if they were arguing with each other), appearing on the page before you.

This has been the view of many, both Jews looking for continuity in their own tradition and for validation of their own culture against the often-dominant Christian culture, and for Christians who want to reconstruct the religious landscape at the time of Jesus. Versions of this (sometimes critically tempered, sometimes not) persist, particularly in religious institutions and some academic institutions. However, it is not that simple, as we shall see.

But what about the statements that aren’t in the name of a Rabbi? This is what fundamentally complicates the former assumption. There is another, unnamed voice in the Bavli Gemara – presenting clarifications or legal rulings, introducing ideas, asking questions, artificially prolonging argument on a point that has been concluded, or, in some cases, cutting off the statement of a previous rabbi and forbidding they speak further (Chagigah 13a). This is the Stam, a term roughly meaning “the plain voice”. The Stam is now widely considered to be the voice of the redactors. It is the voice of the unnamed Stammaim, the late Rabbis (c500 CE to the mid 8th Century), who are not only compiling and bringing together all this disparate material, ordering it, but also editing it, sometimes heavily.3 Sometimes this feels like the composition of the Pentateuch, but the Stammaim are less inclined to preserve clear contradictions, providing additional argumentation to resolve them, and manipulating the text to reconstruct an ideal version, which sometimes requires interventionist editing and the reconstruction of material missing from the various traditions they have inherited. A good analogy for this is the hand at work in what we now call the Deuteronomic History: the books from Joshua through to the end of 2 Kings. In the earlier books, particularly Judges and Samuel, the editors are more hands off : there are stories in those books which are obviously reproduced from earlier sources (we have 2 versions each of many of the episodes early in Saul’s kingship, and both a widely-acknowledged early poetic version, and later prose version, of Deborah’s story in Judges, there is no attempt to force Samson to conform to Nazirite law). However an editorial hand is at work guiding the perspective of the whole, and far more unequivocal in the latter book of Kings, all in aid of a specific perspective, sometimes with an apparently soft touch, but often with an interventionist approach toward a certain conclusion. In some places it can be deduced that the Stammaim have only received the conclusion of the discussion (usually a legal ruling) and are then reconstructing wholesale the entire argument that gets to that point from the Mishnah. They are using what material they have inherited, and building what they can out of it in the form of the kind of dialectical argument they consider to the ideal means of deriving decisions and interpretations.4 In a way, what they are transmitting is not so much content as it is methodology - a way of interpreting, as much as the interpretation itself.

Keep an eye out for this, as commonly you can see this voice constructing the argument of any passage in question. These are very often attempts to reconstruct a presumed-historical argument based on incomplete documentation.

This editorializing can be clearly shown in passages that have parallels in both the Talmudim, where substantially similar material is treated very differently in the Yerushalmi, completed prior to the Stammaic period. The Yerushalmi aims primarily toward conclusion, whereas the Bavli prolongs discussion as much as it can, even when a conclusion has already been reached.5 It can also, sometimes, be seen with the treatment of the same Baraitot in different places, or even within the Bavli itself, when passages are paralleled in two different Tractates. Sometimes statements are attributed to different Rabbis in different places, are unattributed early with a name added in later appearances, or the Bavli version shows clear manipulation of a statement recorded elsewhere toward a different end. There are contradictions, forced resolutions and complex chronological and historical issues. Further difficulties arise on the rare occasions when certain parts of the Bavli can be demonstrated to be products of certain times using historical data. For one example, Michal Bar-Asher Siegal draws a connection between the two minim (“heretics”, in this case Christians) in the story in BT Chulin 87a and the late-4th Century disputes about the Holy Spirit that occurred during the formulation of Christian Trinitarianism, based on the LXX reading of Amos 4:13.6 That story features the 2nd century Rabbinic leader Yehudah Hanasi, but reflects particular, highly specific elements of later Christian doctrinal dispute. A story about a 2nd Century Rabbi appearing to reflect a 4th century environment seriously complicates any assumption that material that claims to be from an earlier period is in fact earlier, or that sayings in the name of a Rabbi can be assumed to be historical. Thus, to make any kind of claim about conclusively dating any constituent part of the Bavli, one must have a clear historical and/or text-critical basis for making that claim.

Next post:

Much of the following discussion is material that I have learned from lectures and seminars, so will not be exhaustively cited. It is, however, largely a summary of the modern text-critical position based on the work of David Weiss Halivni during the 80s, and since accepted and built upon by numerous other scholars. A summary of his work in English is available in David Weiss Halivni, The Formation of the Babylonian Talmud, trans. Jeffrey L. Rubenstein (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, 2013).

It is worth noting the dating of redaction is now widely held to be later than the single sentence on dating in Daniel Boyarin, The Jewish Gospels : the story of the Jewish Christ (New York: The New Press, 2012), which is roughly that of the Amoraic period. Richard Carrier follows this in what appears to be an uncited and inaccurate paraphrase, compare Boyarin: “there are, moreover, traditions in the Babylonian Talmud and thus attested from the fourth to the sixth centuries A.D. (but very likely earlier),” 153; with “Modern scholars are too quick to dismiss this text as late (dating as it does from the fourth to sixth century) since the doctrine it describes is unlikely to be.” Richard Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason For Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), 73. Carrier also appears to be extrapolating a statement about specific passages (including Sanh. 98b, this from 98a and other uncited ones) to the entire Talmud, which is not a claim that Boyarin is making: note the singular “this text” vs Boyarin’s more delineated individual “traditions” (which do not include the directly previous material to the Carrier quotation, which is BT Sukkah 53a-b, which Carrier provides no citation for the dating of and which Boyarin does not consider early, see Jewish Gospels 153 citing only the Yerushalmi version, and 188-9 n19). This explains why Boyarin gives the date he does: He believes these particular traditions are Amoraic (i.e. the two leper-messiah passages, from BT Sanh. 98a and b). There is no indication he conclusively thinks they are Tannaitic, much less pre-Rabbinic. Note also that, somehow, Carrier gives an entirely different date for the compilation of the Bavli in On the historicity of Jesus, 282, again with no citation: “the Jews east of the Roman Empire […] where this Talmud was compiled… from the 3rd to 5th centuries.” This also refers to “references to Jesus being expunged by Christian scribes”, which implies Christians being involved in the pre-printing transmission of the Talmud, of which I have never heard, he’s probably conflating Christian censorship of the Talmud, a phenomenon starting in the High Middle Ages (the prior method was simply book burning) with Jewish self-censorship, in as a means to avoid book-burnings. See my further treatment of this citation here. Neither of these dates even agree with Van Voorst’s popular press book that he says he will follow on dating except where he states otherwise (ibid, 271; one would expect a reason for that deviation and alternative citation to be provided), as Van Voorst gives a rough date of “around 500” (Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament (Eerdmans, 2000), 107. This is in fact given by Carrier on p274, but seems to have been forgotten 8 pages later. Nor do any accord with Peter Schäfer, also cited, who places the “editing” of the Yerushalmi in the 5th Century, and the Bavli reaching its “final form” in the seventh, closer to Boyarin and Halivni (Schäfer, Jesus in the Talmud, Princeton University Press, 2007, 14). Note that even this appeal to Van Voorst is only stated 271 pages in, and thus, if it were to refer to this on page 73, one would have to read nearly 200 more pages to find out where it came from.

Boyarin himself explicitly adheres to the critical Stammaic model in his more scholarly treatment of the same topic, see Daniel Boyarin, Border Lines: The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 151-201. Note his taking up of Jeffrey L Rubenstein, who has “recently argued that many of the aggadot [i.e. narratives] … represent Stammaitic values… [and] almost all of these Bavli sources show evidence of Stammaitic reworking”, (153-4). Martha Himmelfarb is more specific about dating the uncited 98a story, placing it in the 3rd Century, and asserting that this is earliest Rabbinic attestation a messianic reading of Isaiah 53. Martha Himmelfarb, Jewish messiahs in a Christian empire: a history of the Book of Zerubbabel (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2017). 66-8. Halivni places the latest activity contributing to the Bavli in the 8th century, roughly contemporaneous to the book Himmelfarb is treating, Halivni, The Formation of the Babylonian Talmud, 8-11. Rubenstein’s introduction to his edited volume Creation and composition : the contribution of the Bavli redactors (Stammaim) to the Aggada (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2005). 1-20, is a good survey of the current scholarly position on the role of the Stammaim in the Aggadah (i.e. non Halachic/legal content, the latter being the primary focus of Halivni). Rubenstein’s edited volume is available here.

Halivni, The Formation of the Babylonian Talmud, 2–62.

Ibid. 117-154.

Boyarin, Border Lines: The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity, 151-2. Halivni, The Formation of the Babylonian Talmud, 19-21.

Bar-Asher Siegal, Michal. “He Who… Creates the Wind: on b Hullin 87a” in Jewish-Christian Dialogues on Scripture in Late Antiquity: Heretic Narratives of the Babylonian Talmud (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019). 66-108. The paper which became this chapter is available here: https://www.academia.edu/37197969/_Fool_look_to_the_end_of_the_verse_B_%E1%B8%A4ullin_87a_and_its_Christian_background_in_The_Aggada_of_the_Bavli_and_its_Cultural_World_Geoffrey_Herman_and_Jeffrey_L_Rubenstein_eds_Providence_RI_Brown_Judaic_Studies_2018_pp_243_270

And a lecture version of this chapter, including an outline of methodology (but lacking the in-depth examination of sources in the published version) is available here:

Bibliography

Bar-Asher Siegal, Michal. Jewish-Christian Dialogues on Scripture in Late Antiquity: Heretic Narratives of the Babylonian Talmud. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Boyarin, Daniel. Border Lines: The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

———. The Jewish Gospels : The Story of the Jewish Christ. New York: The New Press, 2012.

Carrier, Richard. On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014.

Halivni, David Weiss. The Formation of the Babylonian Talmud. Translated by Jeffrey L. Rubenstein. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, 2013. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199739882.001.0001.

Himmelfarb, Martha. Jewish Messiahs in a Christian Empire: A History of the Book of Zerubbabel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2017.

Rubenstein, Jeffrey L., ed. Creation and Composition : The Contribution of the Bavli Redactors (Stammaim) to the Aggada, vol. 114. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2005.