On How to Read, and How Not to Read, the Babylonian Talmud from a Historical-Critical Perspective (II)

Where we first encounter "innocence of rabbinic textual knowledge" and "the perils of pseudo-historicism" (to borrow phrases from Daniel Boyarin and Benjamin Sommer).

Welcome back, to those who are returning, and welcome to those who are new. This is part two of my ongoing intro to modern critical study of the Babylonian Talmud. The first part, broadly covering the modern critical approach (which you should read before this) is available here:

This is where we get to Dr Richard Carrier, and, following this, we will go over each of the passages he cites, and see what they really have to say from a more rigorous and historical-critical perspective.

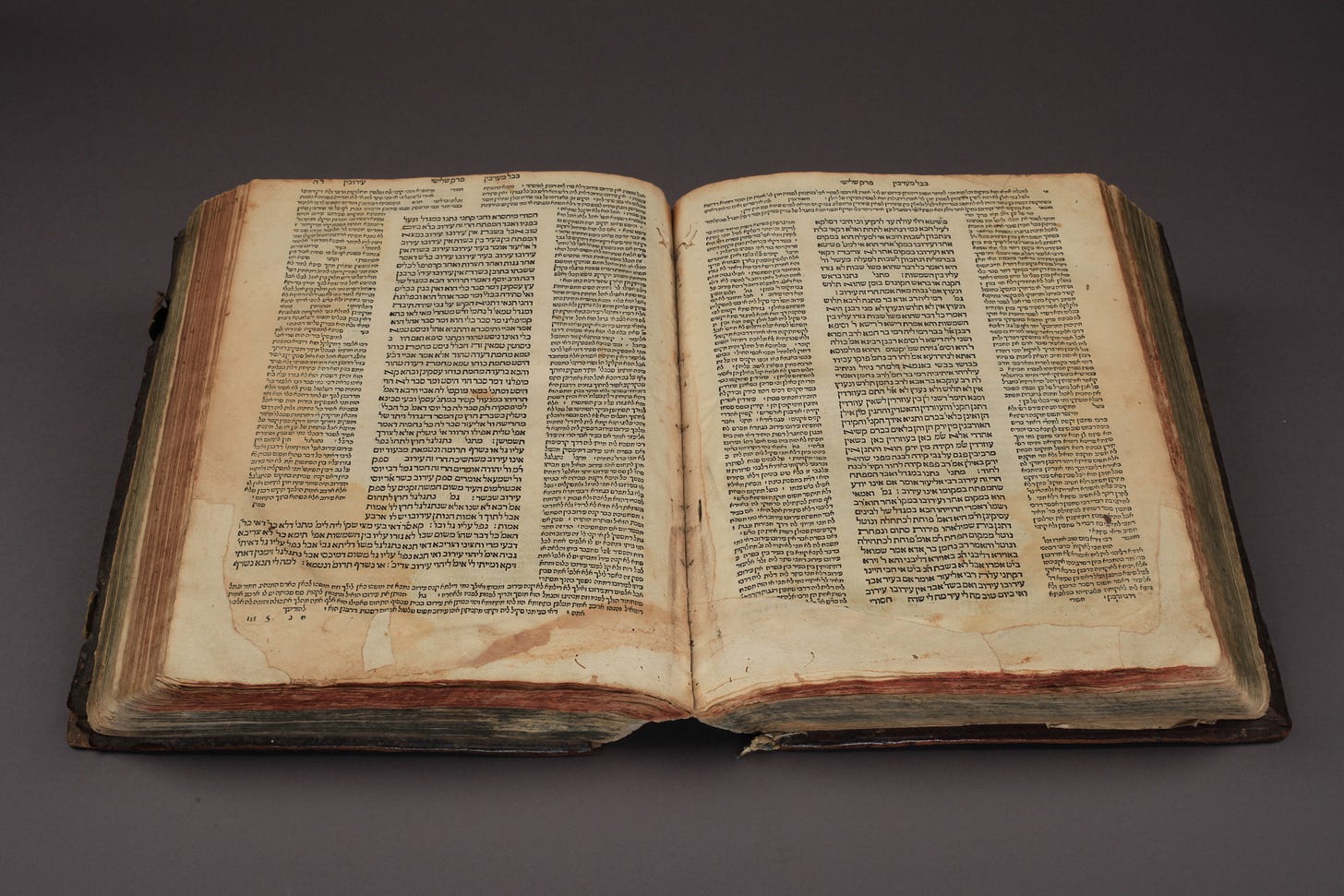

For any student of ancient religious literature very little of this will be surprising. As we are all aware, texts are produced by people in specific historical and cultural contexts, and transmitted, copied, and often edited, by even more people, in more contexts, in relation to other people, sometimes cooperating, sometimes rivaling each other, and the bodies of work they hold are changed and shaped across the centuries by all these contexts and other broader historical phenomena. The Talmud reflects both an early post-Temple Jewish perspective (with claims at 2nd temple representation, though these are worthy of scrutiny), and a later one, across multiple locales, multiple multi-lingual environments (parts are Hebrew, parts are Aramaic, there are many Greek, Latin and Persian loan-words) and multi-religious environments. Pagan, Zoroastrian, and, importantly for our purposes, Christian influences can be seen in multiple places. Christian influence even continues after the text is completed, as for much of its history the most widely available editions were either themselves subject to censorship (such as the Vilna) or based on versions that had undergone censorship by Catholic authorities in the Medieval period. The Vilna edition, the basis for many modern editions, is missing the mention of Jesus in BT Sanhedrin 103a, though this is present in the earlier Bomberg edition printed in Venice, and in manuscripts – the latter holding alternate readings that are incredibly valuable for scholars. Very importantly for this context, many references even to minim (מינים – heretics) were self-censored by Jewish scribes wary of Christian persecution and replaced with Tzadoki (צדוקי) – Sadducees. As the gospels also excoriated Sadducees, these references to heretics, some of whom are clearly Christian, could maybe avoid censorship and the ensuing persecution that often followed, if they were changed to a common enemy who conveniently no longer existed. The only evidence for many changes like this survives in manuscripts.

This is further coloured by the history of Scholarship. Christian scholarship of the Talmud started in the Medieval period and was primarily anti-Jewish, aimed either at proving the Talmud was blasphemous, or that Christianity was true, or both at the same time, as a tool for persecuting or converting Jews.1 Jewish scholarship was primarily religious, and, when the enlightenment arrived, was re-aimed at using the Jewish intellectual tradition to demonstrate its compatibility with enlightenment rationalism as a vehicle for Jewish emancipation. Even in the centuries since, it has primarily been studied for religious reasons, and often treated either as a world apart, representing a purely Jewish, unadulterated tradition, or a tradition which reflects Greek cultural and philosophical ideals (attractive from an enlightenment perspective), or as an auxiliary tool only useful for Biblical scholarship. Before the 20th Century it had rarely been approached on its own from a rigorous historical and comparative perspective, nor from a systematic text-critical one. Rigorous comparative work with Christianity is relatively young, with study of its Persian Babylonian context even younger, and much previous scholarship reflects a naïve text-critical perspective if one is present at all. Even relatively recently there were numerous studies of the influence of Platonic and Stoic philosophy on Rabbinic thought, but religious influence was mostly limited to easy-to-identify anti-Christian polemic, and very little on anything more complex, or from the Zoroastrian side.2 Recent scholarship is far better, but much of this is published in Hebrew and as-yet untranslated.

Two substantial points should now be clear. Firstly, the Babylonian Talmud, as an object of academic scholarship, is not simple, and the text-critical problems it presents if one is to claim that anything within it is representative of a pre-Rabbinic tradition are far, far more complex than they are if you uncritically accept the traditional claim that the Talmud is a transparent record of historical statements. It is also exegetically difficult. The language (or languages, plural) is often terse and cryptic, or relies on wordplay. Variant readings, loan words and grammatical oddities abound. What it looks like it is saying, or doing, is often not what it actually is. Due diligence is required, and often due diligence is far more than is obviously apparent. Though some can be obvious: as the rabbis often say in the stories about heretics: “fool, look to the end of the verse”, meaning “read this passage in context.” Even this is often difficult, as many only read the Talmud through short passages that are translated and excerpted.

Secondly, the history of Talmud scholarship also demonstrates how biases have plagued the field, and, in some cases, have warped the state of scholarship in ways that are only now being thoroughly corrected. Popular beliefs about the nature of the Talmud are likewise plagued by misconceptions. One must be very careful not to reproduce the same errors that previous scholarship, or previous attitudes, have perpetuated. In this way it is very similar to the Bible, in terms of the differences between what it actually represents and what it is thought to represent, and the complexity of getting to what is happening on a textual level and how this relates to the historical context.

Unfortunately, none of these issues appear in the treatment of the Bavli by Dr Richard Carrier. For those who are not yet acquainted with him, Carrier is a proponent of Jesus Mythicism, the idea that there was no historical figure called Jesus. His theoretical alternative for this is that Jesus was originally conceived of as an angelic being, and only later concretized into the human, terrestrial figure we have in the gospels. In order to argue this, he surveys a wide range of ancient religious texts to find the conceptual basis for his model and argues many elements of this are pre-existent in the pre-Christian Jewish tradition, waiting to be realised.

For the record, I have precious little investment in any ideas about Jesus. And, if Carrier were indeed right, I would find it very interesting. However, many scholars have shown his treatment and presentation of the supposed evidence leaves much to be desired. It is often highly speculative, presenting very strange readings, both of primary texts and of the arguments of scholars he cites. I will leave the rest to their respective experts, here focusing only on the Rabbinic material. I was previously unaware of Carrier before Dr Kipp Davis weighed in, and thus alerted me to this treatment. He covered this, as well as the pre-Rabbinic 2nd Temple Period material (and I will defer to him on that), but I want to go more in depth on this as I have spent far too much time recently reading the Talmud.

It is strange that the late-Antique Bavli is considered evidence for his claims. I am confused that he does not stick to first century or earlier, as one would expect that, if his hypothesis were viable, he wouldn’t need to appeal to these texts, as they seem wholly extraneous and likely irrelevant. But he seems to think ideas supporting his hypothesis of Christian origins are represented in the Bavli Gemara, compiled centuries later in Mesopotamia, not Israel. His presentation is perplexing, but also a demonstration of the many common pitfalls in studying the Talmud, often reproduced unwittingly by Biblical Scholars, and thus an opportunity for a methodological study to model how one can, and probably should, study Talmud in a deeper, more holistic and more critically rigorous manner. I have to thank Carrier for spurring me to do this as I have learnt a lot from bringing fresh eyes to passages I thought I was familiar with, there is always something new to learn about texts as dense and complex as these. As we move through the passages he cites, bear in mind the three primary claims he makes about these passages. These claims are made in a chapter presenting “elements” of “Background knowledge” which he states must be as “complete and secure a body of background knowledge as possible” for his purposes, and “should consist of facts beyond reasonable dispute.”3 Of the “Elements” in which this reading appears, he says:

I do not assume such elements are beyond any possibility of debate, only that the evidence is such that the burden must be on anyone who would deny them. The remaining elements I will demonstrate to be true with an adequate citation of evidence and scholarship.4

Then we come to the claims. The first is that:

the Talmud provides us with a proof of concept at the very least (and actual confirmation at the very most). It explicitly says the suffering servant who dies in Isaiah 53 is the messiah (and that this messiah will endure great suffering before his death).

the second that:

The Talmud likewise has a dying-and-rising 'Christ son of Joseph' ideology in it, even saying (quoting Zech. 12:10) that this messiah will be 'pierced' to death.

And the third that, regarding these passages:

only when Jews had no idea what Christians would do with this connection would they themselves have promoted it. There is no plausible way later Jews would invent interpretations of their scripture that supported and vindicated Christians. They would not invent a Christ with a father named Joseph who dies and is resurrected (as the Talmud does indeed describe). They would not proclaim Isaiah 53 to be about this messiah and admit that Isaiah had there predicted this messiah would die and be resurrected. That was the very biblical passage Christians were using to prove their case […] the presentation of this ideology in the Talmud makes no mention of Christianity and gives no evidence of being any kind of polemic or response to it. So we have evidence here of a Jewish belief that possibly predates Christian evangelizing, even if that evidence survives only in later sources.5

Already we have evident problems. Firstly, the only footnotes here are to the referenced folios of the Bavli (two from BT Sanhedrin for the first statement, one from Sukkah for the second, and no citations for the third). There is no supporting evidence provided for these claims, nor direct quotation. Second, concepts are conflated, which we shall see is not warranted. Third, these ideas are presented as “vindicate[ing] Christians,” with “no evidence of being any kind of polemic or response to it” which will be investigated in due course. Finally, the Bavli is compiled substantially after the rise of Christianity and the later Jewish tradition continued to develop and promote these ideas well into the medieval period.6 If this kind of material was anathema, why was it recorded and preserved, not just in presumably older texts but even reproduced and elaborated upon in new compositions? The very book cited a paragraph earlier by Daniel Boyarin documents this and says it was not anathema, as does the Carrier’s immediately-subsequent discussion of Sefer Zerubbabel – and this continues even in the medieval period where tensions between the two respective religions ran increasingly – and occasionally genocidally – high.7

Book burnings were often the result of disputations, and the lesser of two evils when the alternative was burning people rather than books.

If, as cited by Boyarin, Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman (aka Nachmanides or Ramban), could endorse such a reading its supposed vindication of Christianity is not apparent, as he was famously a participant in the Disputation of Barcelona in 1263, in which his apparent victory over the Christian convert Pablo Christiani resulted in his exile from Spain. The Disputation of Barcelona also focused on interpretations of Talmudic passages, including both the leper-messiah passages from BT Sanhedrin 98a and b (the latter of which, cited by Carrier, we will be examining). While Christiani thought these pointed toward the truth of Christianity, Ramban himself rebutted the claim that these have any similarity to Christian beliefs (including on points of basic logic and chronology) - and points out that neither these passages, nor later ones, speak of the Davidic Messiah dying.8 If the similarities between these and Christian beliefs was able to be argued in such a way in the Medieval period, then the situation is most probably more nuanced.

The initial presentation is confusing. The passages are not quoted directly, and there is no analysis, nor citation of secondary scholarship.

So, what does the Bavli actually say in these passages?

There are four clear questions that we need to answer:

Firstly, what do these passages actually say, and are the elements Carrier describes present?

Secondly, are these passages indeed free from polemic or response to Christian claims?

Thirdly, what are the historical claims made by them, when do they claim to be from?

And fourth, how skeptical should we be about those claims?

One would expect a high bar would need to be cleared to accept even those historical claims made, if the same type of claims are doubted for the synoptic gospels, far closer to the events described than the Bavli is to the pre-Rabbinic Judaism of the time in which Christianity originates.

In order to answer these questions we need to take an in-depth look at the passages in question, and their Talmudic context, and the wider context of the rabbinic literature.

Next post:

Or converting and then persecuting them, as happened to many in Spain at the hands of the inquisition following the Alhambra Decree.

There is a good introductory lecture on some of these issues in the history of scholarship by Israel J Yoval here:

Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason For Doubt, 58-9.

Ibid. 65.

Ibid. 73-4.

Boyarin, The Jewish Gospels : the story of the Jewish Christ, 129-56, cited in Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason For Doubt, 73. For these specific points, see Boyarin, 150-6. Contra some claims, Boyarin does not argue this reading is definitively pre-Christian, but rather that the hermeneutic that produces it is, see 186n10, 190n26, note also 187-8n10, and 190n1 to 158-9.

Additional edit: It should not be necessary, but there is a rather indignant clarification of what this citation means to be found here, along with more indignence. I may have got a little ticked off. That “this reading, with all the constiuent parts, that Carrier extrapolates from the Talmud and asserts the Talmud is is independent attestion of, and thus demonstrates is pre-Christian, is not, in fact, something that Boyarin argues is definitively Pre-Christian” should be relatively easy to parse, but not when you’re only provided with the footnote, and thus the demonstrative “this” has no referent. But hey, that’s some random guy on youtube’s idea of best practice, not mine. Funny how those who accuse others of being disingenuous and hypocritical and such things are the ones who behave like this.

Cf. Benjamin D. Sommer, "Dating Pentateuchal Texts and the Perils of Pseudo-Historicism," in The Pentateuch: International Perspectives on Current Research, ed. Thomas D Dozman, Konrad Shmid, and Baruch J Schwartz (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011), 96.:

Some scholars think that a particular theme must date to a particular era; this is the first mistake, which I discussed in the previous section. Furthermore, this example shows that scholars who make the first mistake often commit a second as well: they don’t pause to note that the evidence they used to support their dating could also be used to support some other dating. As a result, one often finds that several scholars who commit the first mistake nonetheless differ in their identification of the one era in which the text must have been written. This second mistake we might term the lack of a control.

The full essay, which should be compulsory reading for any Biblical scholar, is available here.

The other passages include Midrash, such as Eikhah Rabbah 1:51. Note the nuances and complication apparent in the two conflicting accounts available online here, and the Christian one eliding that Ramban recieved a significant payment from the King, but on the subsequent publication of his account, was “advised” that leaving Spain would be good for his health, and copies of his book were burned. It can be seen that Ramban has no qualms about these passages, nor about the linking of the Messiah with Isaiah 53, writing and publishing a polemical treatise about them, and indeed he elaborates further and builds on them in his many biblical commentaries.

Bibliography

Boyarin, Daniel. The Jewish Gospels : The Story of the Jewish Christ. New York: The New Press, 2012.

Carrier, Richard. On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014.

Sommer, Benjamin D. "Dating Pentateuchal Texts and the Perils of Pseudo-Historicism." In The Pentateuch: International Perspectives on Current Research, edited by Thomas D Dozman, Konrad Shmid and Baruch J Schwartz. 85-108. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011.