A Note on Pots and Kettles.

Since I have apparently attracted the personal attention of a certain mythicist.

Hi all, just another “quick” note, but one that needs writing. Or not so quick, this is, unfortunately, long.

I have been informed that I have attracted the attention of Richard Carrier himself, and he is even being paid by someone to respond to my criticisms! That I could be so lucky. If anyone out there would like to throw me a few dollars, let me know and I’ll sort out a method for such. If I could even get a new book or two that would be nice, but either way.

The point, however, that I want to address is nothing so crude as that, but rather technical stuff, considering some of what has been said about me, by someone who as of yet, by his own admission, has not read what I have written bar a few sentences. Firstly, I find it odd that those few sentences, from part II of my series, were selected, rather than this footnote from part I, which I would very much like Carrier to respond to. He certainly should, if he wants to address me with any substance. Likewise all of this, in particular the footnotes. But we’ll get to that.

This is particularly the case if I am going to be accused of peddling “misinformation”. I would far rather prefer any discourse to remain civil, and in the spirit of scholarly collegiality. If this is the start of it, then this doesn’t bode well, but we’ll see. I do not particularly want to be subject to endless streams of insults, as Carrier’s other critics have, but would far rather have the actual substance of what I’m arguing both understood and addressed in a thorough and substantial manner. And, before making such claims, I would echo exactly what Carrier says to all his critics: read my work. Commenting on a handful of sentences and reaching a conclusion from them is absolutely insufficient. He knows this.

Regarding what little (and I mean little) was addressed here though, what I said, was, indeed:

The initial presentation is confusing. The passages are not quoted directly, and there is no analysis, nor citation of secondary scholarship.

There is, obviously more to it, but this is factually correct. Carrier paraphrases the three passages from the Bavli, which I then provide substantial readings of myself in the following installments.

The only footnotes to those paraphrases are the folios of the Bavli. You can look it up yourself. No one else is footnoted there. There is no additional citation for this part of his book (73-4).

But to make matters more confusing, Carrier contradicts himself. As does “Godless Engineer”, who says that Carrier cites Boyarin for these passages. And Carrier then says that what I say is wrong, when I say “this reading” - very clearly I mean the previously quoted one that “Isaiah 53 [is] about this messiah and […] that Isaiah had there predicted this messiah would die and be resurrected”, is something tht Boyarin “does not argue [..] is definitively pre-Christian”. It explicitly isn’t. If he does in fact, “explicitly say” that all of this is preexistent, and if “you can quote him directly on that” I would like to see that quote.

However, Carrier has also been adamant in the past that he only cites Boyarin for the previous material, and, indeed, Boyarin is not footnoted here. And Boyarin’s book only treats one of these Bavli passages (Sanhedrin 98b). The footnote is prior to this. Here are the relevant excerpts from the book:

Element 5: Even before Christianity arose, some Jews expected one of their messiahs heralding the end times would actually be killed, rather than be immediately victorious, and this would mark the key point of a timetable guaranteeing the end of the world soon thereafter. Such a concept was therefore not a Christian novelty wholly against the grain of Jewish thinking, but already exactly what some Jews were thinking - or could easily have thought. This is the most controversial element in our background knowledge, many scholars being so intent on denying it. So I must discuss the evidence at some length, although I shall do this more thoroughly elsewhere.

This is then followed by a footnote:

Richard Carrier, 'Did Any Pre-Christian Jews Expect a Dying-and-Rising Messiah?' [in review]; see also Carrier, Not the Impossible Faith, pp. 34-49 (with a correction: p. 34 arguably misreads Isa. 49.7 [cf. p. 49 n. 30]; as had already been suggested on p. 37). Essentially the same conclusion is argued by rabbinical scholar Daniel Boyarin, The Jewish Gospels: The Story of the Jewish Christ (New York: New Press, 2012), pp. 129-56.1

Carrier has already disabused me of my (i think reasonable) assumption that this is intended to read “Daniel Boyarin argues essentially the same conclusion as the previous work of mine, that Pre-Christian Jews did in fact expect a dying and rising Messiah” (note that that cited paper appears to not have survived review, as I have been unable to find it in any academic database, if it has, I’d love to read it).

Regarding this specific citation I actually had a bizarre exchange with him via an intermediary in youtube comments (would you believe it). I, I think reasonably, read this footnote as above, to which the following reply was relayed to me, by one “bigboi1803”:

To which I replied:

and was replied to (assuming I was a guy, for some reason):

So, what we can gather from this is that Carrier is citing Boyarin for exactly one thing, and that is the suffering (and perhaps dying)2 Messiah tradition, not the Talmud.

Further, he simply can’t be relying on Boyarin for the folios other than Sanhedrin 98b as Boyarin doesn’t address them. Boyarin’s book says nothing about the other Sanhedrin citation (though he addresses a different folio as well, 98a), and only covers the Yerushalmi parallel of the Sukkah material. He doesn’t address the Bavli version of the tradition, except passing mention in a footnote where he excoriates Carrier’s other authority, David C Mitchell’s reading of it, in which he specifically says he considers it late and influenced by Christianity, contra Carrier’s claims.

And Boyarin says nothing like Carrier does, but rather cites them as evidence of the fact that “this midrash”, of a suffering messiah, is not alien to the way that non-Chrisitan, Rabbinic Judaism develops. He doesn’t say a word otherwise in the pages Carrier cites. Nor in the entire book, as I will explain, not that it should have any bearing on this: Boyarin does not say, in the material cited, what Carrier extrapolates from what he cites. And he definitely doesn’t say anything like what Carrier does about Sanh. 93b and Sukkah 52a-b, as he doesn’t say anything about them at all. Carrier also appears to know how Boyarin dates these traditions, since he inaccurately paraphrases, without citation, Boyarin’s dating for the traditions he does address: they are a product of the Amoraic period (fourth to sixth centuries, roughly). This also directly contradicts the two other dates that Carrier gives for the same “text”, as elaborated in my footnote.

So why, then, in his blog response to Davis, does he say this?

that all the points Davis tries criticizing me for are actually just my summaries of leading scholars. For example, my position on reading the Talmud is not based on my own reading of the Hebrew; it’s based on that of rabbinical scholar Daniel Boyarin, whom I cite.

Davis is uninterested in even telling you this—he wants to give the false impression that I just made all this up on my own, and that he’s catching “me” making mistakes, not Boyarin, or his peer reviewers (or mine for that matter).

I, further, have no knowledge to indicate that the New Press, the publisher of The Jewish Gospels, has a peer review system.

But, more pointedly, how can he be relying on Boyarin’s reading of the Hebrew (or, in the case of Sanh. 93, and the bulk of the extrapolation in Sukkah, Aramaic), when Boyarin doesn’t provide readings for them at all?

On the note of peer review however, a number of the scholars he’s gone and found that support him have look like this:

And write books like this:

Or, in the case of Martin Hengel, are praised, on the occasion of his eightieth birthday, in words like these:

There are, of course, others, but this is to say that the citing of numbers of scholars means very little, as Carrier should know. Indeed, he’s a vociferous critic of arguments from consensus or authority himself. Rather than spouting of numbers he should demonstrate what he believes with evidence.

Further, since I have been accused of “misinformation”, I want to be extremely clear about what precisely I am saying. In the material that Carrier cites, Boyarin does not definitively argue for the preexistence of a suffering, dying and rising Messiah. The footnotes I cite are worth quoting, where Boyarin says:

I do not know early evidence outside of the Gospels for this particular way of reading the Daniel material as applying to a suffering Messiah, still less to a dying and rising one, and I have no reason to think that it did not fall into place in this particular Jewish Messianic movement (The Jewish Gospels, 186n10)

“This particular Jewish Messianic movement” is Christianity. He is explicitly saying that the reading of Daniel, that “It is the Christ, Jesus, who is accordingly handed over to the wicked one for a prescribed interval” (144, the page this note is to) is novel to Christianity, and there is no evidence, nor reason, to think it is not.

Next up is:

I am not claiming that therefore the followers of Jesus did not originate this particular midrash, rather, if and when they did so, the hermeneutical practice they were engaged in be spoke in itself the "Jewishness" of their religious thinking and imagination. (190n26)

“This particular midrash” is the suffering, dying and rising messiah. This is a footnote to the passage quoted in the previous livestream, without this foonote. The footnote follows this statement:

As we see, neither Judaism nor Jews have ever spoken with one voice on this (hermeneutical) theological question, and therefore there is no sense in which the assertion of many sufferings and rejection and contempt for the Son of Man constitutes a break with Judaism or the religion of Israel. Indeed, in the Gospels these ideas have been derived from the Torah (Scripture in its broadest meaning) by that most Jewish of exegetical styles, the way of midrash (155, my emphasis).

It is absolutely clear what Boyarin is saying here. He means the way by which early Christians made sense of their belief that their messiah had suffered and died, and, for some, that he had risen again, through scriptural interpretation, was entirely in keeping with the exegetical practices of contemporary Jewish religion. He is saying that the Gospels are midrash. But, also, as per the footnote, that doesn’t necessarily entail this midrash existed before this. This qualification is clear as day, and I have no idea how anyone reads it any other way. Particularly as Boyarin doesn’t substantially address any post-Hebrew-Biblical, pre-Christian texts or beliefs that indicate this in this book. What Boyarin may or may not “really think” does not matter on this issue, as this is about reading comprehension, and adequate and accurate citation.

If you are citing a book for an idea, that idea has to be clearly represented in the material that you cite. And you need to be absolutely clear about who you cite, and what, specifically, you are citing them for.

This is particularly a problem when one puts words in someone’s mouth, as, as I have cited, Boyarin’s scholarly attitude to the Rabbinic texts is far more critical than Carriers. He’s intimately familiar with Halivni’s critical paradigm, and follows it, as I have explained, with extensive citation. He does not believe that rabbinic texts can be taken as prima faci evidence even of the period they describe, much less earlier ones.

The next part of my footnote is prefixed with “note also” – as in “these are not directly connected, but also relevant” – those being his treatment of the David C Mitchell paper that Carrier has described as “in no way incompetent” (Boyarin vociferously disagrees, as do I). “190n1 to 158-9” means “this endnote, which is a note to these pages”. This is notable because those pages immediately follow the pages Carrier cites, and are thus relevant. Those pages are important, as they are highly nuanced, and it is easy to miss said nuance. What he’s arguing against is that the wholesale invention of everything we think of as particularly Christian was ex eventu, with the “eventu” here being Jesus’ death.

On this point I entirely agree with him. But, in particular, I find this convincing because the explanation of Christianity as a response to a series of hallucinatory vision-experiences seems to also be entirely ad hoc. Hallucinations of the departed are common, but this appears to entail significantly more than that, and, further, there has to be both an additional reason that they were considered credible by some, and, additionally, considered incredible, and worthy of absolute rejection, by the majority of Judaeans.

The religious environment in which the movement grew must, necessarily have contained the tools used to create the fully-elaborated religion, but this doesn’t mean all the concepts were there previously, but rather, that the tools to create them were. Indeed, it appears they were not obvious, as one of the biggest problems the early Christian movement faced, and a continual sore spot for them, was the rejection of their beliefs by the vast majority of the Jewish population. This also appears to be the cause for the rapid transformation of Christianity into the Gentile Greco-Roman, universalist religion we know. I would expect that this form, which coalesces around Paul, would be substantially different from what was believed in The Galilee or Jerusalem.

While I am not committed to a particular theory of origins, this latter part in particular is what I believe, and I also believe that this is supported by Boyarin in these excerpts. This may seem to be splitting hairs, but I think it is instead a rigorous treatment based on what we have evidence for. And that the evidence for a pre-Chrisitan suffering, dying and rising messiah is only seen by those who want it to be there (almost exclusively Christians), like Martin Hengel makes me very suspicious of this. This, too, is both ad hoc and, in my opinion, also ex eventu, in that it is conditioned by the normalization of this belief after the (purported) fact. That a significant majority of highly credentialed scholars do not see it is reason for this exact type of caution.

This caution, I want to be clear, is exactly what I’m advising, and which guides my own thoughts on these matters. In the abstract, as I have previously said, I do actually broadly agree with Carrier that there are substantial, endemic problems with New Testament scholarship that desperately require correction. And I have precious little attachment to any of the varied and incompatible results of the myriad quests for the historical Jesus. And this caution, or requirement for carefulness, should also be applied to my work as nothing I have said is a defense of historicism. Rather, it is me saying both that I do not find Carrier’s mythicist hypothesis the slightest bit convincing as an alternative, and I think it is a result of a concerted lack of carefulness in his treatment of evidence, his readings, and his presentation of texts, and particularly an over-reliance on Greek texts which significantly post-date the early-to-mid First Century, like the Church Fathers. Which we will get to in due course. What I am interested in is rigorous historiography. And, for that, you have to have “background knowledge” that is substantially grounded in fact. This is my particular concern with Carrier’s book, which I (and many others) believe is substantially lacking in this.

Thus, since I have attracted Carrier’s attention, he has once again attracted mine. So I have taken notes on the rest of his elements. So I wish to present a challenge to him, if he indeed wants to answer my criticisms. I would like substantial responses to first, the problems I have already raised:

Does “The Talmud explicitly [say] the suffering servant who dies in Isaiah 53 is the messiah (and that this messiah will endure great suffering before his death”? I am pretty sure that I have substantially demonstrated that this is not the case. The (Davidic) Messiah to which Isaiah 53 is exclusively connected suffers, but is not described as dying in any context in which Isaiah 53 is cited, and is nowhere “explicitly” described as dying in the Bavli. This figure dying, unconnected to Isaiah, is hypothetically possible in the Yerushalmi, but this is any entirely separate document and uncited by Carrier, and the Bavli passage that is cited is described by Boyarin (with whom I agree) as explicitly an apologetic reaction to Christian concerns. As I have previously demonstrated, I know of no Rabbinic text making a connection between Isaiah 53 and a dying messiah prior to Sefer Zerubabel. If Carrier has a counter-example I would love to see it.

Would Jews “not invent a Christ with a father named Joseph who dies and is resurrected”? Because this is precisely what Boyarin thinks that the Bavli Sukkah passage is evidence of, particularly as a result of there being no attestation of this name prior to the Bavli. And I agree, as I have elaborated at length.

Does “the presentation of this ideology in the Talmud [make] no mention of Christianity and [give] no evidence of being any kind of polemic or response to it”? I think I have done a pretty thorough job of demonstrating that precisely the opposite of this is true.

To continue, why does he give 3 different dates for the Talmud? And how did this slip past and editor or reviewer?

If he thinks Boyarin is such an excellent scholar, and, likewise, that David C Mitchell is “in no way incompetent”, then does he think the Bavli Sukkah tradition is prior to the Yerushalmi, one, as Mitchell does, or that Boyarin’s criticisms stand? And, if Boyarin is right on this, does that affect his assessment of Mitchell’s competence, particularly given that these criticisms are seconded and expanded upon at length by Martha Himmelfarb? If so, what does this say about Carrier’s initial assessment, showering praise on Mitchell’s work, particularly given the other stuff that Mitchell also argues for? And, on that note, if Mitchell is right about the provenance of Hebrew passages in the Bavli, does that mean the Sotah passages are prophetic, or, more pertinently, does that mean that the Babylonian-educated, third-Generation Amora, Rabbi Assi, also quoted in the passage, is a misattribution? If so, that also raises questions about the attribution to Rabbi Dosa.

If he does stand by his initial presentation of this material, on what basis is he accepting the accuracy of the recording of oral traditions from the first century in the codification of a document the finalization of which occurs six hundred years later (give or take) while simultaneously rejecting the reflection of beliefs from the 30s CE in the late first century-early second century gospel accounts? If the latter aren’t to be trusted for reflecting beliefs less than 100 years old, then why on earth are accounts with half a millennium longer of transmission history, with clear evidence of modification, taken as prima faci reliable? If Christians are capable of fabricating everything whole cloth with no basis in reality at all in less than a century, then surely the rabbis are capable of some creativity as well given 500 years.

On that note, does he, likewise, still affirm that the Rabbis of Babylonia were unaware of Orthodox Christianity, and only had contact with those belonging to the “Nazorian” sect described by Epiphanius? Epiphanius himself only describes the sect as residing in Greece, the Transjordan, and Syria. And besides, if they are a “faithful descent of the original Christian sect”, what are they doing with (according to Epiphaneus), a Hebrew version of the Gospel of Matthew, that Carrier considers a later, historicist deviation from the original version of Christianity? Further, we know the Syriac Church of the East was present in Persia extended their influence as far as the Indian Subcontinent, and the Bavli itself appears to attest to Rabbinic awareness of not only Syriac but also Greek Orthodoxy, but even intra-Christian heresiological debates, as attested by Michal Bar-Asher Siegal. How would it be possible for this to be the case, did Rabbis just not talk to their neighbours? Did no one convert in either direction, and maintain contact with their family? This sure looks like it assumes a social model of complete siloization that doesn’t allow for any kind of social contact at all. That’s just not how societies have ever functioned, and is a level of insularity in complete contradiction with Carrier’s own description of Judaism in the first century - which would, in itself, undercut the idea that traditions from then would be preserved in the Bavli. For that level of social transformation, there would necessarily be a comparable level of doctrinal transformation. This makes little sense at all no matter which way you slice it.

What are the “more reliable Manuscripts” (OTHOJ, 282n4) that disprove Van Vorst’s agreement with Saul Lieberman, the leading expert on Rabbinic MSS of the twentieth century? As Van Voorst says, “The explicit identification of Jesus as Ben Stada comes in the later Amoraic layer” (Jesus Outside the New Testament, 116). This may not be clear to someone without knowledge of Rabbinic periodization, but this is explicitly saying “this only occurs in the later material, from (roughly) the late 3rd to 5th centuries”. That both names are present in Tannaitic material (dating from the first decades of the 3rd century or earlier, namely the Tosefta), without ever being linked to each other demonstrates this. I have provided MSS citations for this (which you can check yourself!), unlike Carrier. Uncensored Talmud MSS such as those cited by Schäfer are no help for this, as his argument is about these names before the Talmudim. So, what are the manuscripts? What specific lines of what folios or Geniza fragments is he referring to? I’d love to know.

And, further, some additional questions that I think warrant answers, given I have now read substantially more of his book, including all the elements of background knowledge that he has presented:

What is the relevance of the end of Malachi being “the very last passage of the traditional OT” (OTHOJ, 68) for pre-Christian Judaism, when that is both a result of the Christian ordering of the books, and the Christian adoption of the codex, rather than the “books” that became the Tanach being a series of separate scrolls, which they were for Jews at the time, and continued to be so into the Islamicate period?

Why should we assume the veracity of significantly later, Patristic Adversus Ioudaios accounts of the corruption of scripture by Jewish scribes (90-2; and 141ff, which reads like the apologetics of the Church Fathers, in particular Justin Martyr and Origen), particularly when there is parallel evidence of Christians doing precisely that themselves, and the earliest copies we have of much of the Greek Biblical text are from the 4th C CE or later? Would it not be more reasonable to examine each specific instance, and look for independent attestation before taking the Church Fathers at their word, particularly when this level of skepticism is precisely what Carrier demands regarding other textual evidence?

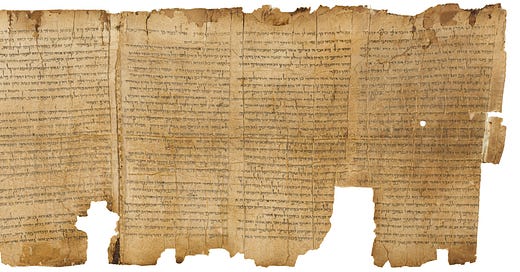

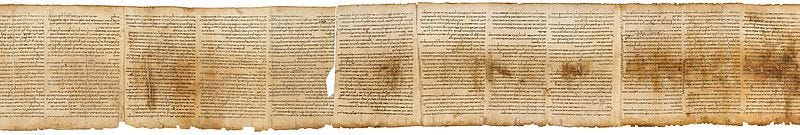

Is he aware that his purported citation of the Hodayot (1QH; OTHOJ 111n114) from Robert Price is, by Price’s own admission, paraphrasing the English translation of Wilfred Watson? This paraphrase is exceptionally free and includes the wholesale insertion of phrases, iconography and ideas absent from the original document. The words חלב and בשר (“milk” and “meat”) do not occur in the text in either of the cited hymns, and Price’s paraphrase, particularly of the first cited Hymn, is bizarre given Jewish dietary laws. Unsurprisingly, I checked the original, and what Price writes is simply not there. The paraphrases of Price bear only the slimmest resemblance to the original text, and, working from academic editions, it takes considerable effort to identify precisely what parts of the text he’s working from, as a substantial proportion of the “hymns” is a product of his own, highly creative imagination. There is nothing in the first citation (Col XV, 6ff) like the negative clause regarding meat that Price inserts, and the second (XIX, 18-23) is about contemplating human mortality, contrasted with divine mercy. It contains nothing about children: that is entirely an interpolation by Price. These metaphors don’t even exist in the translation Price is working from, which would have been easy enough to check, as it is directly cited by Price. Should this be considered a reasonable citation of evidence for an academic study, or due diligence?

On a similar note, what is he talking about in this footnote (91n62)?

Again, the Qumran version of Isaiah (1QIsaa) says 'he was wounded for our

transgressions, he was pierced for our iniquities . . . it pleased Jehovah [sic] to pierce him. . . to make his life an offering for sin' (which in effect means the same thing in English as 'he was nailed up for our iniquities . . . it pleased Jehovah [sic] to nail him him up').

This is obviously addressing Isa 53:5 and 10. This is the MT for the first of those verses:

וְהוּא֙ מְחֹלָ֣ל מִפְּשָׁעֵ֔נוּ מְדֻכָּ֖א מֵעֲוֺנֹתֵ֑ינוּ מוּסַ֤ר שְׁלוֹמֵ֙נוּ֙ עָלָ֔יו וּבַחֲבֻרָת֖וֹ נִרְפָּא־לָֽנוּ׃

the NRSV renders it thus:

But he was wounded for our transgressions,

crushed for our iniquities;

upon him was the punishment that made us whole,

and by his bruises we are healed.This is what 1QIsaa has:

והואה מחולל מפשעינו ומדוכא מעוונותינו ומוסר שלומנו עליו ובחבורתיו נרפא לנו

which translates as:

And he was wounded for out transgressions and crushed by our iniquities, upon him was the punishment [or discipline/chastisement] that made us whole, and by his bruises we were healed.

the only additions are either vav as the conjunction, a terminal ה on the initial pronoun, and spelling variations adding vowel-letters to make the text easier to read phonetically. The verb that Carrier reads as “pierced” is a general verb meaning to wound, kill or slay (or two different things, as we will find out).

It is also the first verb in the sentence, the second unambiguously means “crush”. Carrier’s got the word order wrong, so this is already inaccurate.

This is verse 10 in the MT:

וַהֹ' חָפֵ֤ץ דַּכְּאוֹ֙ הֶחֱלִ֔י אִם־תָּשִׂ֤ים אָשָׁם֙ נַפְשׁ֔וֹ יִרְאֶ֥ה זֶ֖רַע יַאֲרִ֣יךְ יָמִ֑ים וְחֵ֥פֶץ ה' בְּיָד֥וֹ יִצְלָֽח׃

NRSV:

Yet it was the will of the Lord to crush him with affliction [or illness].

When you make his life an offering for sin,[e] (meaning of Hebrew uncertain)

he shall see his offspring and shall prolong his days;

through him the will of the Lord shall prosper.Here is 1QIsaa:

וה' חפץ דכאו ויחללהו אם תשים אשם נפשו יראה זרע ויארך ימים וחפץ ה' בידו יצלח

This is more difficult, as particularly is the second clause (as per the NRSV’s notes). It looks like it should have several prepositions, but doesn’t. Roughly, it reads:

And the will of the Lord was to crush him, and חללה him, [that] if you place [your guilt on his life / the guilt-offering of his life] he [may/will] see his offspring and lengthen [their? his?] days, and the will of the Lord by his hand will prosper.

This is a significantly more literal reading of much of the same syntax that is rendered as above by the NRSV (note that, while mostly reliably literal, this is also a Christian translation). It can be rendered multiple ways (the particle אם could even be “though” or “despite”). This is a difficult passage either way.

However the question in this case is how to render the only difference from the MT: the verb ויחללהו. It could, once again, mean wounded, though the orthography is strange. However there are two other options presented by all the scholarship I have consulted. The first is that, thematically connected to the rest of the passage, it is like the MT this is being stricken by disease following other variant uses of חל״ה. However, there is also the reading presented by CR North, and followed by Klaus Baltzer in his Hermeneia Commentary on Deutero-Isaiah (392-426, this discussion at 410 and 419-20). He, likewise, sees the MT as an alteration, but what has been removed is not “piercing”, but rather the very common meaning of חל״ל, to profane. This is particularly convincing to me as it follows the only other occurrence of that particular spelling in the MT (Lev 22:8).3

To read “piercing” in this text, much less that this unambiguously “means the same thing in English as he was nailed up for our iniquities . . . it pleased Jehovah [sic] to nail him him up” is completely unwarranted. This not a straightforward reading of the text, even if we put aside the fact that the word which can mean “to piece” very often describes generic wounding of various kinds, which do not involve piercing, impaling or anything similar. And the same spelling occurs meaning something completely different elsewhere in the Bible. This looks like another a post facto reading, of the kind heavily favored by Christians (as with Psalm 22:16) which is not obvious, or clear, presented as if it would unambiguously be so to anyone reading the text without prior conditioning. That so many similar examples in Carrier’s book are drawn from Christian writers, and/or supported by the citation of explicitly Christian scholarship, makes it achingly ironic that Carrier accuses his opponents of Christian apologetics.

You may have noticed a pattern here, which is precisely what I want to emphasize - Is the data, the assessment of evidence, the background knowledge and historical awareness that Carrier demonstrates sufficient to level the kind of radical challenge to biblical scholarship and religious historiography he is making? My opinion on this, at least so far is twofold. Firstly, when it comes to criticizing previous scholarship, particularly of the New Testament, Carrier makes a series of very pertinent points. I am with him when it comes to that, a lot of the time, NT scholarship just isn’t as rigorous as it should be.

However, in making those points, and in proposing an alternative to the model of Christian origins generally accepted, Carrier ends up himself reproducing the same kind of mistakes, and repeatedly so. I think this laundry list of errors, the majority of them on matters of fact rather than interpretation demonstrates this. And, in saying so, again, I am not defending any position here: Not one of the objections I have raised rests on that. It should be obvious, as none of these objections have anything to do with Jesus or the New Testament at all. So, with that, I will await a reply.

Yet another additional note added late: the reading in NTIF is indeed a misreading, and grammatically impossible, the “Holy One of Israel” is the speaker, and “the despised” the addressee, this is clear from the prepositional ל in the verse and no other reading can be made. Likewise, Psalm 89 is a lament, the citation of 50:4-9 (39) appears nonsensical given the content of v6, and the sentence this is a note to, that “the idea that a Chosen One of God must suffer total humiliation and execution at the hands of the wicked is a major theme in Isaiah” (34) generalizes the content of the suffering servant to the entire book, beyond even Deutero-Isaiah, conflating terms used even within this later text to describe the Deity, as per 49:7, with terms describing the people of Israel (41:8-9; 43:9, 20; 44:2, 49:7, 65:9, etc) and even the equation of this with the Messiah is a projection, given the sole use of this word in 45:1. That this appears to have been written prior to consulting any secondary scholarship on the question other than Christian apologists and theologians, given the lack of citation thereof, makes it appear that such scholarship he cites later is an attempt to bolster a conclusion already arrived at, rather than that conclusion being drawn a survey of scholarship on the question. Or from consideration of the terminology used in the Hebrew. And as per the subsequent discussion, even Daniel Boyarin vehemently disagrees with the position here, which explicitly argues that the entire narrative of Jesus is described here and was understood to explicitly describe a suffering, dying and rising messiah, and asks “how could any Jew not have understood this to mean that a righteous, wise, chosen servant of God would be wrongly despised, convicted, and executed, and in so doing save Israel from its sins and afflictions?” (39) Unfortunately this appears to be exactly what happened, as Paul is having to wrestle with this problem in Romans (10:14-21; 11:7-10, 13-24). Carrier appears to have conceded some of this and rolled back somewhat, however understanding that this is a stepping back from a previously uncompromising position, conceding some details, though also only acknowledging the error in the interpretation of a single verse (given its clear ignorance of both Hebrew grammar and biblical idiom) tells us something important, I think. That this, and the other article (which appears to have died in review) are the “evidence” is in tension with both the hedging of the paragraph, and the far more cautious position of Boyarin - and the simultaneous citation of Boyarin and a book chapter which is almost entirely scriptural exegesis, quoting Isaiah from the NKJV, and reading the book exactly as later Christians would is remarkable.

An additional note, in addition to all the ones I have already given, is yet another explicit qualification - one which, if I remember correctly, Carrier also later clarified, that he is indeed only citing Boyarin for the suffering part. What my footnote says is that he doesn’t argue the stuff that Carrier says is in the Talmud, and is evidence of pre-Christian belief, that is “suffering, dying and rising Messiah attached to Isa. 53” is pre-existent. This is from the opening to the chapter on this very issue:

That the Messiah would suffer and be humiliated was some thing Jews learned from close reading of the biblical texts, a close reading in precisely the style of classically rabbinic interpretation that has become known as midrash […] the most distinctive innovations of Jesus himself or his followers can be found in the religious literature of the Jews of the time of Jesus or before. […] Many Jews were expecting the divine-human Messiah, the Son of Man. Many accepted Jesus as that figure, while others did not. Although there is precious little pre-Christian evidence among Jews for the suffering of the Messiah, there are good reasons to consider this too no stumbling block for the "Jewishness" of the ideas about the Messiah, Jesus as well. Let me make clear I am not claiming that Jesus and his followers contributed nothing new to the story of a suffering and dying Messiah; I am not, of course, denying them their own religious creativity. I am claiming that even this innovation, if indeed they innovated, was entirely within the spirit and hermeneutical method of ancient Judaism, and not a scandalous departure from it.

This point of the "Jewishness" of the vicarious sufferings of the Messiah can be established in two ways: first by showing how the Gospels use perfectly traditional, midrashic ways of reasoning to develop these ideas and apply them to Jesus, and second, by demonstrating how common the idea of a suffering and dying Messiah was among perfectly "orthodox" rabbinic Jews from the time of the Talmud and onward. My reasoning is that if this were such a shocking thought, how is it that the rabbis of the Talmud and midrash, only a couple of centuries later, had no difficulty whatever with portraying the Messiah's vicarious suffering or discovering him in Isaiah 53, just as the followers of Jesus had done? (133-5).

Note the following:

this is primarily about hermeneutics, not pre-existent ideas. It is about how to get the ideas, not already having them. They can be extrapolated from scripture, but are not already there. The purity law that is described in the Gospels (including full-body immersion) is not the plain reading of scripture. It appears to be an innovation of the 2nd C BCE. Likewise with the prohibition on mixing meat and dairy, what exactly counts as work on the Sabbath and so on. These, too, are derived from biblical texts, but are not immediately apparent.

Likewise, there is no explicit claim of anything pre-existing other than perhaps a suffering messiah. As above, Carrier has (from memory) already acknowledged this (though it definitely isn’t the most intuitive reading of what is found in his book). I am not so sure Boyarin is right about this, but the point I was making, which is abundantly clear from context, is that he, explicitly, does not claim that the entire matrix of a suffering, dying and much less rising messiah is pre-existent. Which is true. He also doesn’t think it’s a marked deviation from authentic “Jewishness”, on which I will remain neutral. But, even so, he is unsure about this. note the continual talk of “innovation”. His primary point is that this is Jewish, not that this is not novel. Like much of Boyarin’s scholarship (the previously cited Harvard lecture series on Enoch and Metatron, his voluminous other publications on the Son of Man and Two Powers in Heaven) what he is arguing for (if not entirely clearly) is continuity within a chain of development. One link, clear from this, between whatever is prior to Christianity and the Talmud is…. the gospels. Thus it is nonsensical to extrapolate from this that the Talmud attests to a pre-Gospel set of beliefs (which should be obvious to anyone familiar with the literature, but appears to not be). This is what Boyarin’s wheelhouse is: tracing the way a tradition develops and transforms itself in marked ways that look like discontinuity, and showing the relationships and chains of transmission between things that look markedly disconnected from one another. He is also, unfortunately, prone to a lack of clarity, as, if you follow his work, you will know there are long series of clarifications and qualifications in trails of essays following his major academic works. But that’s neither here nor there.

There is, indeed, precious little evidence for a pre-Christian suffering messiah. In fact I know of none, much less for a dying one. All the evidence that is purported to show that is spurious, or extremely uncertain, and open to significantly different interpretations that appear far more reasonable.

Note specifically what Boyarin is very clear to say he is presenting the Talmud as evidence for: that this is not a “shocking” exegesis, and not anathema to Judaism. And, in marked contra-distinction to Carrier, he reads the Gospels as the primary evidence, and this as the secondary, following them. It is also striking that the Rabbinic emphasis is clearly different than the Christian one: it is on disease and illness (a part of Isa. 53 that the Christian version elides completely). That he does in fact think that the Bavli Sukkah passage is evidence of apologetic reaction to Christianity (as he explicitly says in the footnote that I have cited many times) evidences the fact that he is not arguing for the same thing as Carrier at all. If this is where Carrier got the idea, then I’m very surprised, as Boyarin’s entire career evidences the fact that he’s perfectly aware that the Rabbis of the Talmud are very familiar with Christian thought, and, indeed, highly influenced by it. Thus, if he is attempting to paraphrase Boyarin when he writes that “only when Jews had no idea what Christians would do with this connection would they themselves have promoted it. There is no plausible way later Jews would invent interpretations of their scripture that supported and vindicated Christians” (OTHOJ 73) he has fundamentally misunderstood Boyarin, and shows a profound disfamiliarity with Boyarin’s work, and Rabbinic scholarship in general. Literally no one thinks this. Much less Boyarin, who thinks that Mashiach ben Yosef is, precisely, evidence to the contrary.

Thus, it is absolutely clear that he “does not argue this reading” - i.e. “Isaiah 53 to be about this messiah and admit that Isaiah had there predicted this messiah would die and be resurrected” - “is definitively pre-Christian” - definitively being the operative word - “but rather that the hermeneutic that produces it is.” As per my footnote.

A second update in the form of a footnote, which I just thought of dozing in the very early morning: This reading, which Baltzer considers original, and thus reads מחלל in v5 as being a corruption, makes a lot of sense, and hilights a difficulty with reading this servant song as being about Jesus that I haven’t seen articulated before: the language used makes sacrifice much less atonement impossible. For one to be sacrificed one has to be “without blemish” (this is included in every law of sacrifice in Leviticus). This is in marked contrast with even the MT, with the use of the word חלי (disease, v3), but particularly נג״ע (v4, 8), often translated at “stricken” but very frequently used regarding a plague or pestilential disease like lepra. It occurs 60 times Leviticus 13 and 14 according to BDB. Likewise, if this reading, with חלל is original (Blautzer reads it back into v5 as well), a sacrifice is “holy to the Lord”, the antonym of חלל, which means profane, blasphemous, etc. This, in fact, demonstrates the opposite point that Carrier wants: reading Christian doctrine out of Isa. 53 is actually remarkably difficult and counter-intuitive.