On Reading the Talmud: A 21st C. Non-Eschatological Coda

In which I elaborate my thesis and reflect on what has been, what I hope has been learnt, and Kohelet.

Finally, the end - but for an annotated bibliography. That’ll be soon. In advance of that, here’s an ominious stack of books beside my desk:

Here’s the whole series:

Well, that took longer than I thought, the earliest version of this, as per last time, was completed at the end of my mid-semester break, and, following extensive editing, cross-checking references, finding more extremely strange assertions, checking those and so on I am now entering exam season. But it is worth pausing a moment to reflect.

It may be surprising, particularly to him, that the genesis of this project was not Richard Carrier. My encounter with his work just sparked something that I already had a bunch of notes on, which is a deep perplexity with the way in which particularly some New Testament scholars approach the Talmud, often betraying not just, in Boyarin’s words, “an innocence of Rabbinic textual knowledge,” or broadly of modern textual criticism, but beyond that even a fundamental misunderstanding of what the Talmud is and what it does. Many treat the Talmud as if it were simply a depository of generically “Jewish” opinions, and take a statement from the Bavli as emblematic of some point relevant to the New Testament, divorced from context. In some cases, even a marginal opinion that is rejected in the Talmud is cited as representative. And that, from a text composed centuries later and markedly different from any given in the Mishnah or Tosefta, texts far closer to the period in question, and thus of more relevance – though they themselves still require robust methodological treatment. This can even entail (as we have seen with Mitchell) misidentifying a legal discourse as a theological one, on top of failing to ascertain both the historical context of the argumentation and its purpose – and how both of those differ from those of the Yerushalmi, The Mishnah and Tosefta, and the early Halachic Midrashim (i.e. Sifre and Sifra). Often this simply feels like point-scoring, or an appeal to authority in order to bolster the “authentic Jewishness” of Jesus, which was never in question, but is of a markedly different character from the Rabbinic culture codified centuries later.

As this has been on my mind, seeing a single place where most of these problems are present, in a – if you will forgive me – “one stop shop” – sparked me to write what I intend as a guide to avoiding those pitfalls. In this way Carrier and I are, on at least one issue, on the same side – we both think at least some proportion of New Testament scholarship leaves much to be desired and is missing crucial safety rails necessary to prevent it from descending into a discourse of pure self-justification. Thus, in offering a corrective to him, my intent in doing so is to simultaneously offer a broader correction to everyone else, some of whom really need to do better.

Thus, I want to make this explicit, in case the nuance has been lost in the mess of readings, citations, interpretative arguments, and so on:

The thesis of this entire project is to provide a methodological model. As per the title of this series, albeit abbreviated in later installments: this is about how and how not to read the Babylonian Talmud from a historical-critical perspective. Implicit in this is how (and how not) to marshal the Bavli, and the Rabbinic literature in general, as evidence for a historical argument, and what the background knowledge about composition and redaction, cultural and historical context is that needs to be accounted for prior to presenting an interpretation as evidence toward a particular historical point.

This is the precondition for it being admissible as any kind of evidence, or, for that matter, of considering something probable, or even possible. That something was imaginable in late antique Babylonia, as a baseline, has about as much bearing on the first century (or the 1st BCE) as that Christians considered a child Jesus making birds out of clay plausible. And a failure to imagine the rabbinic stories as a product of Jewish-Christian competition is just that, a failure of imagination – it is, in fact, telling that Carrier takes these stories as being so successful in undermining the credibility of the accounts in the gospels that he marshals them as evidence against them – that is, very obviously, a strong indicator that they could well be one of the most successful anti-Christian polemics ever written – so successful that they work even now, 1500-1300-ish years after their redaction and/or composition (give or take).

It is far too easy to assume a naïve view of vague and inchoate “oral traditions” (from when? About what?) and thus pick any random, decontextualised statement (or worse, a harmonization of various parts) and cite it to make a point. This devolves into something that is primarily rhetorical, as well as fundamentally flawed, regardless of what that point is – even if it did happen to be correct, you haven’t shown how, why, and on what grounds it should be considered as a reasonable assertion – particularly when compared to the manner in which other, far earlier texts are treated.

This is why I began with an admittedly crude comparison to the textual history of the Bible – while there is a near-universally accepted level of background knowledge of text-critical theory required for marshaling any Biblical text as evidence for anything, most biblical scholars – indeed most non-specialists in general – don’t have the first idea about what the parallel knowledge, theory, and methodological considerations are for the Rabbinic lit, and thus treat them similarly to someone who thinks that the Biblical accounts of the united monarchy of David and Solomon is a reliable historical account. Thus they become merely something to mine for prooftexts, rather than an object of study in their own right, and of interest in themselves for what themselves are doing – which, to my mind, is far more interesting. Even regarding Jesus, what the Rabbis were saying in Persia, in dialogue and cultural competition with their Christian neighbours, is incredibly interesting. It says very little about 1st Century Roman Judaea, but that doesn’t negate what it says about nascent religious orthodoxies in Late Antiquity and how they defined themselves, and shaped themselves, and influenced one another.

Likewise, doing the work of tracing ideas back from the Bavli, through the Yerushalmi, the Midrashim, the Tosefta and Mishnah – this being the requisite work for demonstrating validity of a historical point – is both important and interesting in itself. But this means acknowledging discontinuity and the way any idea is changed and shaped by the various contexts through which it moves. Often, that itself is the important historical data that is uncovered – what looks like continuity, what looks like the preservation of something ancient, is as much something that has been fundamentally transformed by the process of transmission, to the point of being almost unrecognisable. This is one of the things this is foundational to study of the Bavli: the more you read the Bavli in dialogue with careful examination of the earlier strata of the Rabbinic literature, the more you see the incredible level of novelty and creativity the Bavli records: taking one Mishnah and, in the process of explicating it, often changing what it “says” in such dramatic ways that, at times, what the Rabbis of the Bavli take from it Is unrecognizable when compared with the original Mishnah. We have got a taste of this in our examination of Bavli Sukkah.1

All that being said, on a far more general level, the most important lesson is about careful reading, and about reading beyond one’s assumptions. Reading the Talmud by itself is like trying to read the Bible by itself, but harder, with more complex historical-critical issues, a lot of which are significantly more opaque than they are for the Bible. As it is less narrative, and more dialogical, not to mention primarily concerned with often arcane matters of religious law, it is harder to spot textual problems – there are less moments like Noah’s Ark, the sale of Joseph, or the Theophany at Sinai in which there are clear, easily identifiable indicators of a composite text – nor is it like the Gospels which present clear narrative contradictions, most obviously in the Passion narratives. It is further harder to identify some markers if one is not reading the original languages, as transition of dialect, language or even simply syntactic indicators of formal parts is seldom signposted in translation. In part because of its mystery, and in part because of the historical tensions between Judaism and Christianity, and in part because of the sheer complexity and assumed knowledge in much scholarly work, there is less widely available scholarship on its textual issues, nor its historical value. It is also easy, if careless, to missunderstand the point a secondary text is making. Much of the more accessible work is over-simplistic, because the answers are extremely complicated and often inconclusive, which is never going to have popular appeal, and resists accessible explication. It is also hampered by specialization: scholars of early Christianity often read Greek and Latin, and maybe Biblical Hebrew, but not Mishnaic Hebrew nor Aramaic, and vice versa, and institutions tend to be insular, and specialities become silos. This exacerbates the already-present problems, and makes correction difficult as one needs to know the texts to know the textual history and understand the requisite critical methodology.

History, too, is extremely important. Many problems find an easy remedy in some basic historical periodization, and being aware this was written earlier than this, and this may appear to fill in blanks, but may not necessarily be doing so (after all, we have all those infancy gospels). And if this was written here, at this time, the environment it was written in contains these demographics, occurs so long after this event, and so on. If we take all these texts as somehow floating ahistorically, it is easy to connect this part to that part, but, if we historicize them – a necessary step for any theory to have historical value – then it is not so simple. This, ironically, means checking your work. And that checking is complicated, and difficult. Particularly if one hasn’t shown one’s working – and I’m sure I’ve made mistakes as well. I hope they are minor (Agadic Midrashim and Targumim are not my forte), and easily remedied given that I have shown my working (albeit in often interminably long footnotes). I will accept any corrections gladly.

Comparative religious historiography is far more complicated than it looks, too. There are two assumptions that must be dispensed with before doing serious work in this field: the first that religious thought is necessarily naïve or simple, which is an assumption of many whose only exposure to such has been contemporary evangelicalism – a lot of this stuff is extremely baroque and complex, as is its historical context and content – as well as, often, being fundamentally alien. The second is that being “outside”, so to speak, makes one immune to the kinds of hermeneutic strategies employed traditionally within religion, the most obvious of which being things like eisegesis and apophenia. Very often we want certainty, or, at least, a coherent narrative. But a large proportion of the evidence we have is highly fragmentary, there are enormous lacunae, and we want to make a certain kind of sense of it, and, in the process of doing so very often create meaning that is not inherent in the evidence before us: as Benjamin Sommer writes regarding the Biblical texts, often, given our evidence, the best we can say is “this is pre- or post-exilic” and live with that uncertainty. The failure to do so, or to selectively apply criticality to one text, while failing to do so to another, leads to what Sommer calls a “lack of control” in which methodological inconsistency causes the proposed conclusion to defeat itself by way of its own incoherence.2 Of many of the texts he is addressing, all attempts thus far to say more than that rely on clearly circular arguments. Just as we must be sure of what we know, we must also know what we don’t know. Or, conversely, the historical value of them is not so much what they say, or the claims they make, but rather why these texts, composed in this particular historical and cultural environment, would say the things they do about the past.

This is a worthwhile principle to generalize: without evidence we can produce more systematic meanings, but in doing so we must always be aware that these connections between dots are a product of our thought, and our discourses, and do not necessarily exist within the texts we draw them from. These connections have to be demonstrated.

That speculative level, and rigorous historical criticism are different domains, one can inform one the other, but without clear, concrete and coherent argument they cannot be conflated; if they are, we revert to pre-criticality. Gaps in our knowledge must be acknowledged, if not there is no difference between our work and that the Medieval period, and we have learnt nothing. This is generally framed as the fundamental challenge of modernity to traditional religious thought, but here we see that it applies just as much in the domain of secular history. Religion and reason do not map onto two mutually exclusive poles one to one, while the presence of the former all too often can indicate the absence of the latter, lack of the former does not indicate presence of the latter.

Thus, argument from “this thing looks like this other thing” is woefully insufficient – even as an argument for the relationship between texts. Resemblance is entirely relative, and can be the result of multiple factors, including simply coincidence. One only needs to look as far as Christian responses to Buddhism generally,3 and then, later specifically to Japanese Pure Land Buddhism,4 to see how easy it is to make mistakes based on simple resemblance, and what issues can then arise as a result of those mistakes. Even if a dependency relationship is established, which direction the causal relationship goes in is often not clear-cut. Texts also absolutely require reading in context, and careful analysis of their relationships to the surrounding environment and culture, as how something should be interpreted is often dependent on the types of hermeneutical strategies favoured by the group in question at the time in question, which may deviate markedly from what initially appears to be the simple meaning. Word use, too, depends on such things – “this word always means this specific thing” is not necessarily the case either, as can be seen by the migration of terms from the pre-Exilic period to different connotations in the early Rabbinic period.5

Perhaps surprisingly the fundamental problem here is, I think, exactly the type of problem that Carrier identifies, but fails to present a viable solution to: when it comes to religious culture, it is very easy to sound credible and convincing, particularly when so many are psychologically primed for particular kinds of conclusions, but very hard to actually be demonstrably right. Particularly as being right often runs counter to the assumptions embedded in popular religious culture. One should, indeed, be sceptical of received wisdom and convention – but be equally sceptical of those peddling alternatives, as they are just as, if not more, liable to fall into error. Those who sell answers to problems, rather than advising caution, and lack of grounds for certainty, or simply saying “things are far more complicated than this,” or “we can’t really be sure of these things” are often selling false certainty. When it comes to people who are certain in the face of much reason for caution, always ask how, and check their sources.

But, in the meantime, when we re-hash the same old sub-Hegelian historiography:

So, after Sommer:6

next post:

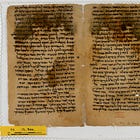

At the risk of over-emphasising my point, I will again hold up a big sign pointing to this footnote. The rejection of the reading given by Van Voorst, cited again by me from Lieberman here, much like the acceptance of David C Mitchell’s reading over that of Boyarin addressed at exhaustive length here, and in my previous reading of the Sukkah tradition, is both predicated in innocence of the structure of the Talmud (Carrier seems to just not understand what Van Voorst is saying at all) but also a denial of historical methodology in general. It requires not only simply taking the Bavli Germara’s explications at face value, but willfully ignorning the logical problems that are presented in the text itself, just as Boyarin says that Mitchell’s reading must say the text is tannaitic, despite it saying the opposite. The other addressed traditions require the same: Just as there are serious narrative problems trying to read the various gospel accounts as recounting the same narrative, we have exactly the same textual difficulties here, compouned by two different attempts, in the BT and TY respectively, to harmonize disparate material to different results - but, further, we have that disparate material surving without harmonzation in the prior source, that being the Tosefta. This is not hypothetical, like Q or the “oral traditions” of which he is so disparaging regarding Goodacre. To flex a little, I have actually looked at the manuscripts, and the name Ben Stada occurs in Tosefta Shabbat, Erfurt MS, 27r, 27, just above the 2nd gap from the bottom before “אחד” on the right); Vienna 58r, 25-6 (end of the line starting with a large indent has בן the next line opens with סטרא, note that this MS has a ר whereas the other has a ד, following Bavli Sanh. 67b vs TY Yevamot). There is no co-occurance of Ben Pandira or any similar name, which, as previous cited, is in Chullin, in MS at Vienna 227r, 12 (Erfurt does not seem available for this). If he has access to “better” manuscripts that confirm either of the disparate Bavli harmonizations they appear to be uncited by any scholar of which I’m aware.

Sommer, "Dating Pentateuchal Texts and the Perils of Pseudo-Historicism." 106; 94-101.

See, for example, the assessment of the Rev. Timothy Richard’s translation of the Awakening of Faith, in the introduction to the more recent translation, Aśvaghoṣa and Yoshito S. Hakeda, The awakening of faith : attributed to Aśvaghoṣha, Translations from the Asian classics, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), 10-11.

The similarity of cosmic soteriological figures and centrality of trust/faith has been noted by many, though the development of the veneration of Amitabha can be traced entirely independently, step by step, back to the early stages of the development of Mahayana, and variations of this were encountered in multiple places by early Christian missionaries, in some cases to much confusion.

Bar-Asher Siegal, Heretic Narratives, 109-142 presents a strong argument regarding the migration of the term בעולה, and that the latter meaning of the term can be seen in Paul’s citation of Isaiah 54:1 in Galatians 4:21-31. The paper which became this chapter can be found here. Likewise, putting aside the whole “manufacturing” thing, anyone assessing Carrier’s assertions about the use of words should look them up in a concordance: if “σπέρματος” means “sperm” (an anachronism in itself), then what is it doing in Gen. 1:29 as something produced by plants, and, more pertinently, Gen 24:60, where Rebecca’s σπέρματος is spoken of. (The answer is that it is the standard word to translate זרע, with a meaning spanning from “seed” to “descendants” and everything in between and used whenever that appears). Likewise for Carrier’s assertion that “[Jews] would never invent a Christ with a father named Joseph” ( OTHOJ, 73, glossing משיח בן יוסף); ben can mean “son” but has a far wider valence, here meaning “of the line of”, as with “ben David”. To limit the word to son makes the majority of uses of בני ישראל, b’nei Yisrael, nonsensical, and implies that Judah, Ruben, Joseph, Benjamin etc were involved in the entire narrative from Exodus through Joshua, and that every priest ever named had the impossible parentage of both Levi and Aaron, as well as Jacob/Israel, being their direct biological fathers.

Sommer, "Dating Pentateuchal Texts and the Perils of Pseudo-Historicism." 108.