On How and How Not to Read The Talmud (V) Suk. 52a-b.

On the Mashiach ben Yosef tradition in BT Sukkah 51a-52b and the parallel in TY Sukkah 5:2

Welcome back to this long series thing. Apologies for the delays, but I have been both busy and ill, and submitting a lot of my final assignments. Now that’s done, you can also look forward to a long paper on legal traditions in the Pre-Rabbinic period, and a review of Yonatan Adler’s The Origins of Judaism: An Archeological-Historical Reappraisal. Please read the previous installments of this series:

We are, finally, past the half-way mark, or a bit further. This is the last of the citations, there will be some analysis that follows (including covering the Midrashic passages associated with what we have here) and some wrapping up. But without further ado:

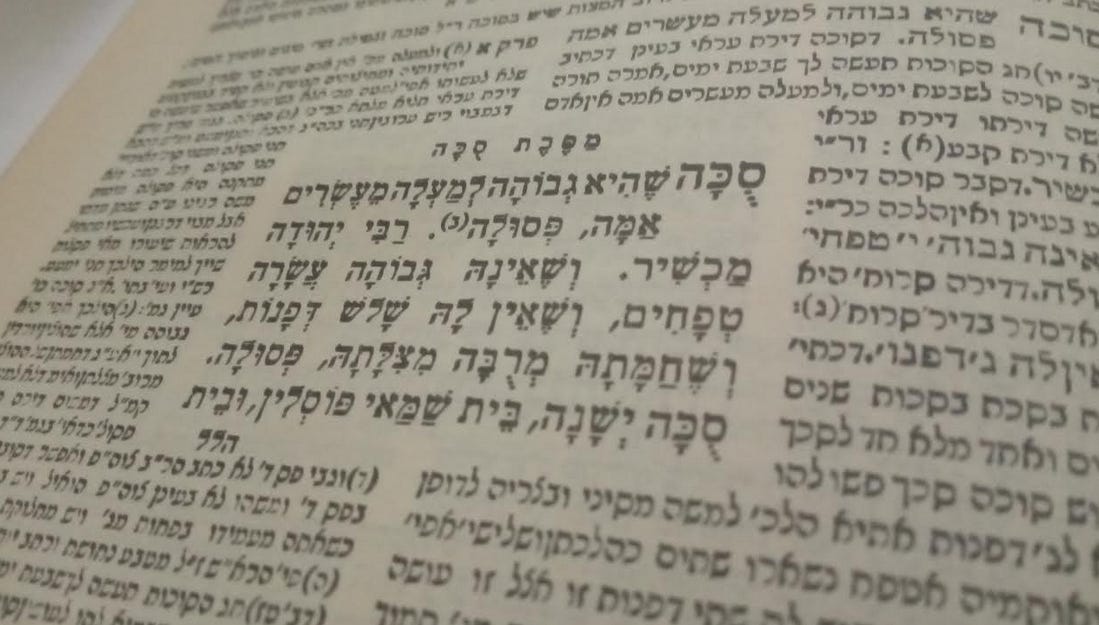

The final citation is from a different tractate, in a different order. This is Sukkah 52a-b. The Mishnah this is the Gemara to (5:4, quoted on 51a-b) is not particularly relevant to our discussion, it covers part of the festival ritual as practiced when the temple stood, and laws of gender segregation. The Gemara opens with a recounting of that, and other glories of the past, before Israel was humbled, and the celebration in that Mishnah is then tempered by the presence of the Yetzer Hara – the negative impulse that leads people to sin, which is taken as the reason that the temple was destroyed (and the purported justification for said segregation). This single section deals with Mashiach ben Yosef: the Messiah, son of Joseph, i.e. of the northern tribes of Manasseh and Ephraim, a general metonym for the Northern Kingdom of Israel that was destroyed by the Assyrians. There are two occurrences of this name here. This is introduced in this broader discussion of the Yetzer Hara. It is worth emphasising that is our first encounter with this other Messiah, who is not from the line of David. The Davidic messiah has been the subject of the entire discussion in Sanhedrin, and, in that entire tractate, the name Joseph (יוסף) does not occur a single time, there isn’t even a mention of the son of Jacob with his famous robe, or a Rabbi or other character with that name. There is further no other occurrence of this name, “Mashiach ben Yoseph” in either Talmud, or I am unaware of a single mention in any of the earlier literature. Late-antique Midrash does have a figure who comes to be identified with this figure. This will be addressed in the next installment.

The full section is as follows, starting from the end of 51b: (Steinsaltz translation’s gloss from Sefaria preserved for context):

The Gemara asks: How could one do so, i.e., alter the structure of the Temple? But isn’t it written with regard to the Temple: “All this I give you in writing, as the Lord has made me wise by His hand upon me, even all the works of this pattern” (I Chronicles 28:19), meaning that all the structural plans of the Temple were divinely inspired; how could the Sages institute changes?

Rav said: They found a verse, and interpreted it homiletically: “The land will mourn, each family separately; the family of the house of David separately, and their women separately,” (Zechariah 12:12). They said: And are these matters not inferred a fortiori? If in the future, when people are involved in mourning and the evil inclination does not dominate them, the Torah says: Men separately and women separately; now that they are involved in Celebration, and the evil inclination dominates them, all the more so [should they be separate].

This is the initial problem – is changing the structure of the temple correct? The reason for the change is an arcane matter of gender segregation. A prooftext is brought (by the amora Rav) for that change, but this is related to mourning. An interpretation is offered, based on the passage being part of a messianic prophecy, which requires further interpretation – involving the Yetzer Hara, the reason gender segregation is required in the first place.

what is the nature of this mourning? Rabbi Dosa and the Rabbis disagree concerning this. One said for Messiah ben Yosef who was killed. And one said for the Yetzer Hara that was killed.

Granted, according to the one who said Messiah ben Yosef who was killed, it is written “And they shall look unto Me because they have thrust him through; and they shall mourn for him, as one mourns for his only son” (Zechariah 12:10). However, according to the one who said for the evil inclination that was killed, does one need to mourn for this? one should conduct a celebration. Why did they cry?

The problem: if this one, mourning is demonstrated by this verse, but if the other, why would they mourn? This still doesn’t seem to make sense in the context, much less with this interpretation. Rabbi Dosa, a Tanna, attested in the 2nd C, is named here, bringing a dispute, and creating a temporal disjunction with the Amoraic Rav. There is a further problem with this attribution however, as we shall see. Further, the prooftext brought here by the Stam (12:10) elides the house of David, both in the initial verse introduced, and this quotation. This will be relevant for the Yerushalmi parallel.

as Rabbi Yehuda taught: In the future, G-d will bring the evil inclination and slaughter it in the presence of the righteous and in the presence of the wicked. For the righteous [the Yezter Hara] appears to them as a high mountain, and the wicked it appears to them as a strand of hair. These weep and those weep. The righteous weep and say: How were we able to overcome so high a mountain? And the wicked weep and say: How were we unable to overcome this strand of hair? And even the Holy One, Blessed be He, will wonder with them, as it is stated: “So says the Lord of hosts: If it be wondrous in the eyes of the remnant of this people in those days, it should also be wondrous in My eyes” (Zechariah 8:6).

This helps though – the mourning – over the Yetzer Hara, not the Messiah (that interpretation is shelved in order to elaborate this one) – precedes the celebration – and it is backed by a prooftext from the same prophet. There is one more sentence on that topic:

Rav Asi said: Initially, the evil inclination is like a strand of a spider’s web [bukhya]; and ultimately it is like the ropes of a wagon, as it is stated: “Woe unto them that draw iniquity with cords of vanity, and sin as if it were with a wagon rope” (Isaiah 5:18).

But then we get to the relevant passage, returning to the Messiah:

The Sages taught: To Messiah ben David, who is destined to be revealed swiftly in our time, the Holy One, Blessed be He, says: Ask of Me anything and I will give you, as it is stated: “I will tell of the decree; [the Lord said unto me: You are My son,] this day have I begotten you, ask of Me, and I will give the nations for your inheritance” (Psalms 2:7–8). Once [He] saw Messiah ben Yosef, who was killed, he says [to the Holy One, Blessed be He]: Master of the Universe, I ask of you only life; [He] says to him: Life? Before you spoke [this] already your father, David, prophesied about you as it is written: “He asked life of You, You gave it to him”.

Note that the first idea introduced is Mashiach Ben David. He is speaking to the Deity, who quotes back to him a verse from the (traditionally Davidic) Psalms. Also note what is missing (here in square brackets, those words from the psalm are not quoted). The clause of the psalm which contains “you are my son” is omitted – even though this statement would be directed entirely to the Davidic Messiah. Altering a quoted verse in such a radical way is notable.1 But then we move to a dead messiah, but this dead messiah is, explicitly, not Davidic. He is not even of Judah, but rather from the lost northern tribes. Further, the passage is situated after the death of this messiah, and all discussion of him is mediated through the Davidic messiah. Mashiach ben Yosef can’t resurrect himself. If he is resurrected at all, which is far from clear, this is dependent on the appeal on his behalf by the Davidic Messiah to the Blessed Holy One. If resurrection is implied in the psalms citation the implication is that his resurrection will occur at the dawn of the Messianic era, when universal resurrection was expected.2 But this psalms verse could equally be a reference to a previously given life, or, more strikingly, to the life of the soteriologically effective messiah, Mashiach ben David (who the life was given to is not clear). The perfect aspect here (describing completed action), both in the reference to David and the life that is given, נתתה (you have given, not you will give), makes this more ambiguous – verses are more likely to be read as prophetic if they are in the imperfect, describing uncompleted action – as we saw at the end of the previous reading from Tractate Sanhedrin.

Note that this is what follows from an extrapolation of mourning over a messiah, from passages in Zechariah that explicitly refer to the house of David, then moves to mourning over the Yetzer Hara, then to this, which is an elaboration on a previously rejected exegesis (mourning over a messiah, the Yetzer Hara is what has been elaborated on), following an extensive explanation of the accepted one. The Bavli, rather than accepting either, wants to make both work together.

And…. the anecdote just ends. There’s no description of what happens next. This section is complex and ambiguous, but whatever way you read it, this is not a vindication of Christianity. And, crucially, in relation to the dying Mashiach ben Yosef there is no citation of Isaiah 53. There is no clear reason to extrapolate a connection between this passage and the passages from Sanhedrin.

A more direct connection can perhaps be drawn to the Yerushalmi parallel. There is no explicit lineage here, only “the messiah” connected to that verse from Zechariah. That passage reads, in the same context of changing the temple given above:

From where did they learn [this]? From words of Torah: “The land shall mourn, each family by itself [The family of the House of David by themselves, and their womenfolk by themselves; the family of the House of Nathan by themselves, and their womenfolk by themselves]” (Zechariah 12:12). [there were] two amoriam, one said: this mourning is for the Yetzer Hara. The other said: this mourning is for the Messiah. To he who says this mourning is for the Messiah, if in this time they are mourning, [if you] say the men are by themselves and the women are by themselves, how much more so when they are rejoicing? To he who says this mourning is for the Yetzer Hara, the Yetzer Hara is no more, how much more so [is it necessary that] the men by themselves and the women by when there is Yetzer Hara?

This appears to be the earlier version, and the dispute is between Amoraim, with the (earlier) Tanna Rabbi Dosa absent, as is the name Mashiach Ben Yosef. The Zechariah verse is not brought by Rav, as in the Bavli. There is no additional discussion on this point, it just returns to discussion of the temple. The prooftext is brought, two different interpretations are given, and rather than them being weighed against each other, a a fortiori argument (kal v’chomer in Hebrew, “from the light to the heavy”, i.e. analogy from the lesser case to the greater, as in “if in this case where it seems less significant, this law must surely apply in the more significant case”) is presented for each. Either reading supports the legal issue here, so there is no need for an elaboration, or even to decide which is correct. As both prooftexts work in theory, the theoretical correctness is enough, the prooftext is accepted even though the verse retains ambiguity. There is no Stam here, as this is not the Bavli, and thus none of the further exegesis. From this we can safely assume that Rabbi Dosa is a late attribution, as, probably, is Rav. Thus, there could be a entirely hypothetical dying messiah, going back to the Yerushalmi, in a statement claiming to be from the 3rd-5th Century, post-Mishnaic period. But only that far. This is also unconnected in any way to Isaiah 53. The presence of the Messiah also appears to be a simple exegetical move from the Zechariah verse – the passage already makes use of the unquoted separation of men and women (this is the reason it is brought in the first place) – so why not ask the further question, why would the house of David be mourning? There is no context of an elaborate scenario of eschatological expectation here unless the reader brings it themselves. But however one interprets the passage clearly the Bavli is dependent on this single, simple statement for its far more elaborate exegesis of Zechariah, as it reproduces this dispute, and, unlike the Yerushalmi doesn’t settle for the a fortori halachic argument. The Bavli wants the correct exegesis as well. It takes the exegetical question – from “house of David in mourning” to “mourning a messiah” seriously - apparently more seriously than the halachic question, the answer to which is assumed to be normative. Clearly there is not a single thing in this text that suggests the existence of any non-Davidic Messiah. In fact the text itself seems predicated on the Messiah being Davidic.3

Daniel Boyarin latches onto this, and, on the basis of this, reads the later more elaborate Bavli version as an explicitly apologetic move, negating (or, at the very least, revising) this previous statement that an unqualified messiah will be mourned, in disputing interpretations of this verse given by two unnamed amoraim (i.e. rabbis from the 3rd-5th Century).4 I would go further and suggest that this is the reason that no further exegesis is required – it’s not presented in anyone’s name and thus not certain in its authority.

The Bavli Gemara then continues on the original theme, which is the nature of the Yetzer Hara, going through other biblical descriptions of it, citing other prophets, and so on, and the reason for exile and the destruction of the temple. The conclusion, before the next Mishnah is cited, follows (52b):

“The Lord then showed me four craftsmen” (Zechariah 2:3). Who are these four craftsmen? Rav Ḥana bar Bizna said Rabbi Shimon Ḥasida said: Messiah ben David, Messiah ben Yosef, Elijah, and the righteous Priest. Rav Sheshet raised an objection: If so, that which is written “And he said to me: These are the horns that scattered Judea” (Zechariah 2:4), these are coming for their enemies.

Rav Ḥana said to Rav Sheshet: Go to the end of the verse: “These then are come to frighten them, to cast down the horns of the nations, which lifted up their horn against the land of Judah to scatter it.” Rav Sheshet said to him: [Literally: “With him in Aggadah [i.e. non-legal discussion], why me?” Steinstalz glosses as: “Why should I disagree with Rav Ḥana in matters of Aggadah, where he is more expert than I, and I cannot prevail?”]

“And this shall be peace: When the Assyrian shall come into our land, and when he shall tread in our palaces, then shall we raise against him seven shepherds, and eight princes among men” (Micah 5:4). Who are these seven shepherds? David in the middle; Adam, Seth, and Methuselah are to his right; Abraham, Jacob, and Moses are to his left. And who are the eight princes among men? Jesse, Saul, Samuel, Amos, Zephaniah, Zedekiah, Messiah, and Elijah.

Here we get to the meat of what the Stam is doing with this eschatological passage. The extrapolation on the Yerushalmi’s ambiguous interpretation, brought back in the previous section, returns here, with a specific goal in mind – harmonizing both interpretations and working out a way they can both be accepted. This passage is working out who multiple eschatological figures are, the Four Craftsmen from Zechariah, and the Seven Shepherds and Eight Princes from Micah, to create an eschatological scenario that synthesizes all the disparate pieces. This shows a clear development from earlier material, and part of that development is the insertion of Mashiach Ben Yoseph into this framework.

The differences between the Yerushalmi and the Bavli heavily imply the exegesis of the Bavli is an attempt to reconstruct a discussion the Stammaim (the anonymous redactors of the Bavli) believe previously occurred, probably starting from the Yerushalmi’s single statement, drawing from independent exegesis of other parts of Zechariah, initially accepting the mourning over the Yetzer Hara, then returning to the rejected interpretation (which would be superfluous for the Yerushalmi – the conclusion there is “either works”) – and the second section with the Psalms quotations is, essentially, anonymous. There is no evidence that it is historical, nor any other attestation of this tradition. The original, single dispute, naming just “the messiah” in the context of a verse that mentions the house of David is probably Amoraic, given its presence in the Yerushalmi, but no claim can be made beyond this. The third century Rabbis named in the Bavli provide no dating, as we have already seen inaccuracies in attribution, and none of this material is independently attested. This appears to be a clear example of the process described By David Weiss Halivni in his description of the Stammaic reconstruction of Halachic disputation, assuming the two Amoraim described here were discussing a pre-existent Tannaitic interpretation that was lost and thus reconstructing it. This involves the insertion of both attribution and the specification that the one who is mourned is not the Davidic Messiah, but an independent figure, in congruence with latter ideas but assuming they are older. The entire subsequent exegesis is predicated on this reconstruction of missing material, including an interpretation that was left uncertain, yet there is no evidence that it is not entirely a projection of later assumptions back into the Tannaitic period for the sake of further baroque exegetical elaboration. Every feature of this passage bears the hallmarks of the Stammaim.5

next post:

This is particularly notable in comparison to the early MSS tradition of the Gospel of Luke, which originally contained a quotation of this very verse, later removed apparently to avoid the adoptionist Christology that was implied by the part of the verse retained here: “on this day” implied that Jesus was not the Son of G-d prior to his baptism. See Bart D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture : The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996) 62-7. That this reading is preserved until the early 5th century indicates that it may have been known to the Rabbis. However, even the correction, which harmonizes the verse with the text of Mark, could be read as being polemicized against in this passage: it elides the sonship, but retains the temporal begetting. I am unsure of any way to account for this elision other than some kind of apologetic awareness of Christian Christological claims. If this were not a concern, one would expect the verse to be quoted in full.

As per the previously cited Mishnah Sotah 9:15, and many other rabbinic sources: “and the resurrection of the dead comes through the prophet Elijah, may his name be remembered for good”, with Elijah interpreted as the herald of the Messiah (Malachi 3:24, cf. John the Baptist in the Gospels). This is the basis for Elijah’s presence in the continuation of the text, cited below.

i.e if not for the Messiah being Davidic, the prooftext does not imply this point at all. Why would the house of David mourn for a messiah from the house of Joseph? This is an incredibly important observation, and overlooking this has warped much earlier scholarship on this question. Jeffrey Rubenstein cites an important paper to this point by Shamma Friedman, in which “Friedman argued that historians must identify the ‘literary kernel’ of rabbinic traditions before making judgments about the historical kernel. He repeatedly pointed out how scholars had mistakenly based conclusions on data culled from traditions within the Bavli despite the fact that the original versions of those sources preserved in the Palestinian documents lacked that data. These historians, in other words, based their conclusions upon literary reworkings of no historical worth”. Friedman, Shamma, לאגדה ההיסטורית בתלמוד הבבלי, ספר הזכרון לרבי שאול ליברמן, ed. Shamma Friedman (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary, 1993), 119–63; cited in Rubenstein, “Introduction”, in Creation and composition : the contribution of the Bavli redactors (Stammaim) to the Aggada. 5-6. Cf. David Mitchell, "Rabbi Dosa and the Rabbis Differ: Messiah ben Joseph in the Babylonian Talmud," Review of Rabbinic Judaism 8, no. 1-2 (01 Jan. 2005 2005), https://brill.com/view/journals/rrj/8/1-2/article-p77_4.xml. 82-3.

Boyarin, The Jewish Gospels : the story of the Jewish Christ. 188-9n19.

Halivni, The Formation of the Babylonian Talmud, 24-6 (note that both footnotes and translators notes are important here). Note that this is a description of halachic argumentation (he states that Aggadah is attributed) but this analysis demonstrates the presence of the same patterns in Aggadah, as have many other scholars. There is a significant bibliography of this scholarship in the translator’s notes to these pages, see also the work of Michal Bar-Asher Siegal. In said translators’s notes, Rubenstein writes: “That the Stammaim contributed so extensively to the Aggadah ultimately supports Halivni's claim that most of the Talmud is of Stammaic provenance” (270). There is a citation of the anthology of studies of Stammaic contributions to Aggadah available here: https://www.academia.edu/3681854/_Creation_and_Composition_The_Contribution_of_the_Bavli_Redactors_Stammaim_to_the_Aggada_ed_Jeffrey_L_Rubenstein_T%C3%BCbingen_Mohr_Siebeck_2005_

Cf. Boyarin, Border Lines: The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity, 163-5, interpreting the famous Aggadah from Eruvin 13b as a statement of Stammaic methodology.