On "Paul Within Judaism"

After Adam Kotsko

I posted a note responding to this post by Adam Kotsko a while back:

That note (which you can read here) was inspired by a dispute I had on bluesky, and I want to add something to this, as the conversation about this again blue up (ha ha) and ended with me being blocked by someone on said platform, probably for blowing up said person’s notifications on thanksgiving (which may have been rude, but I am not American, so did not realize at the time, but then again it was him who re-ignited said conversation in the first part). But I’ve been chatting to some other people, far more knowledgeable about Christianity and Paul, and put together some more remarks. I still think Kotsko is right, but he’s more right in more interesting ways. Here’s my summary of the issue now:

While I should be clear that I do like a lot of the ideas that have come out of PWJ, I have a lot of problems with elements of the general framing, and the way that the perspective has been leveraged and/or manifest in certain circles, particularly by people like Gabriele Boccaccini and others from the Enoch Seminar, in both their work on Paul and their extension of the paradigm to cover the entire New Testament, even entirely anonymous works by authors whose ethnicity we cannot know, who often polemicize against hoi Ioudaioi. There was an interesting moment in one of the Enoch Seminar zoom panels where a question was asked, that, given we cannot know who wrote these documents, if John is “within Judaism” then what is to stop someone reading Justin Martyr’s Trypho or Origen’s Contra Celsum “within Judaism” and the fact that a clear rationale couldn’t be produced should give anyone pause. While it is that extension that most concerns me, the issues start with PWJ.

One of the weirder things in PWJ stuff is the insistence that Paul wasn’t “exceptional.” He’s no longer a “radical Jew” but just a Jew. That he was a Jew should, by now, be a trivial observation. However, fairly obviously I think, this insistence on him not being “exceptional” is itself treating him exceptionally, because a) as a member of an elite, highly literate class, and as a sectarian to boot, he pretty straightforwardly was, and b) no one has ever tried to argue that Moreh Hatzedek was somehow just an ordinary Jew - crucially because no one has needed to, as the exceptionality or lack thereof of Moreh Hatzedek has no bearing on any living tradition. The insistence that adjudicating who is and isn’t Israel and sectarian bickering was somehow “normal” (a claim I have directly encountered) is the product of a warped perspective in which there is an unusual focus on what is and is not “normal,” and an insistence that this question be answered by the surviving literature, and everyone knows the record is incomplete, and the process by which literature survives itself is affected by numerous factors that skew it. In the case of the late Second Temple period that record primarily consists of the literature of two sectarian groups: The Christian New Testament and the documents from Qumran. Crucially, it is insisted that this be the measure of what is and is not normative, and not what your average Jew on the ground was doing (see Adler on this, for example, and the final footnote of that review). Given that there is an insistence on this issue at all, and on the adjudication of it based exclusively on sectarian documents, rather than any investigation into what the vast majority of Jews were doing, and their day-to-day lives and their various engagements with their religious tradition, I cannot help but think that it is a reasonable conclusion that the reason people are insisting on things like that lies in the social context of the scholarship making those claims, not the Eastern Mediterranean during the first century (and, quite probably in a desire to refute the claim that Paul was theologically exceptional).

The key contradiction is that this perspective wants to have its cake and eat it too: “let Paul be weird,” but he was also just a regular Jew, so you can’t call him weird (which seems an awful lot like equivocation: the first weird is relative to us, the second being within his historical context). In the piece I was originally responding to, Kotsko said:

There’s a similar disconnect in the notion that Paul’s “only” critique of his contemporary Jewish brethren was their rejection of Christ. Oh, so you’re saying he thinks they’ve merely missed the most important thing ever to happen in human history? No big deal! Other than that, he presumably views himself as completely in continuity with the tradition of his birth—except for the part where he’s actively preaching to non-Jews and forbidding his Gentile followers to take part in any distinctively Jewish rituals.

Now, one can quibble with “the most important thing to ever happen in human history” but he was at least to my knowledge the first Jew to ever commit to writing a belief that the messiah had already come. That is a really remarkable thing, and as fundamental a difference from every other Jew in existence as the Qumran sectarians’ rejection of the Jerusalem temple - if not more. As a historical fact that sets Paul apart from what the vast majority of other Jews were doing at the time, and its bad history to not acknowledge that for what it is - but it is a desirable position for many contemporary liberal Christians to blunt the exceptionalism of that, because there being a line between them and Judaism makes them uncomfortable, and they’re not a fan of the consequences of what Boyarin describes as “making a difference” between Christians and Jews.1

But, in the articulation of this kind of solution to that problem, they have to assert a lack of normativity, and that what the early Jesus movement were doing was “within Judaism” and that the consequences of that further down the track were some kind of unfortunate accident, and that in itself means taking control of the adjudication of what is and is not Judaism, eschewing the idea of normativity, asserting, strangely, that it was normative to be a hypersectarian rejecting core beliefs that the rest of the community had, or Paul asserting that Jews’ understanding of their own religion had been metaphysically impaired by divine fiat (Rom 11:25) , and so on. Here Christians (and the vast majority of NT scholars are Christians) get to be the ones who adjudicate where and when the border is drawn (or, for secular scholars, Christianity becomes the yardstick by which what is and is not “regular Judaism” is measured). Thus it is implicitly, unilaterally announced that those beliefs and activities of the followers of Jesus, and which became central to Christianity were (and thus, implicitly are), again to steal a term from Boyarin, “Jewish doings” (and not particularly unusual - or “exceptional” ones at that) - the undoing of the “making a difference” ends up being a projection of Christian difference onto everything else as normative, without saying it.

And the weird thing about this is that none of this is necessary. Just letting profoundly sectarian documents be profoundly sectarian, and letting sectarianism have its regular definition as a small group who break away from the norms of a larger population in no way obscures the cultural function of these documents, nor does it occlude any feature of their historical context.2 This, even more importantly, would still place Paul within Judaism - just a highly particular sectarian strand of Judaism that was beginning the process of differentiating itself from all other forms of Judaism by way of a project of self-definition by othering those outside of it. It is that observation - that this is unnecessary - that leads me to the conclusion about this stuff that have reached.

Now, I’m not saying that everyone is actively engaging in this, or that for everyone this is conscious, but this is how it plays out, and I think that last bit is the psychological mechanism behind it - it’s yet another manifestation of the profound cultural Christianity and Christian normativity of biblical studies. To argue that there’s no motivation couched in modern social politics behind this tendency is not only absurd, but would make this the first movement in biblical criticism in all of history to be entirely without such an influence. In Pauline terms previous scholarship would have been sown as a physical body, yet raised as a pneumatic body, entirely freed from the corrupting influence of base material flesh to which all scholarship is normally subject.

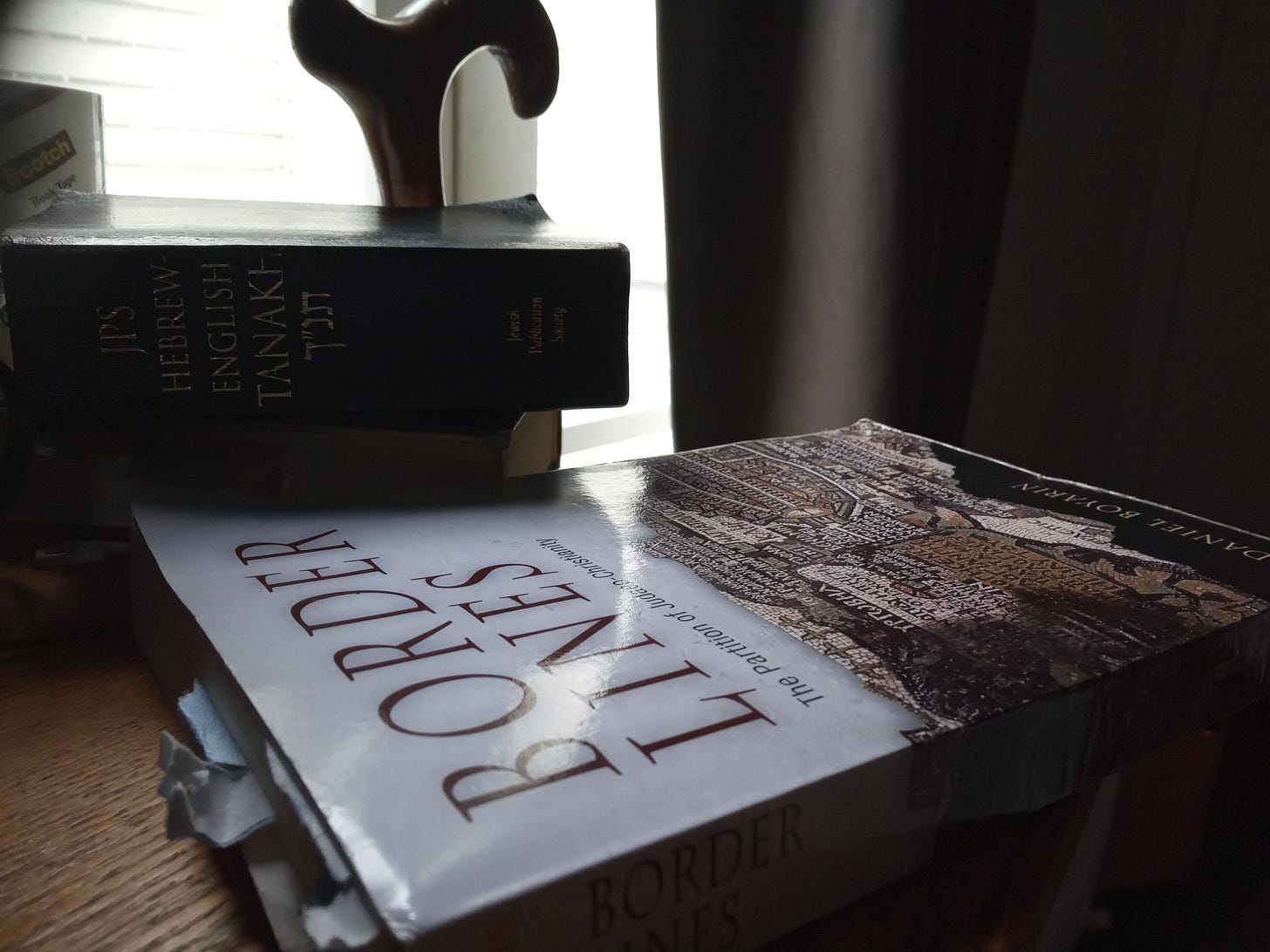

That being the title of a chapter in Border Lines. Apologies for not citing stuff fully, I’m typing this up in my browser. Boyarin sees this as emerging in the 2nd Century, but I think it’s pretty clear that its happening already in the first. Adelle Reinhartz’ work on John demonstrates this, and I think it’s also active in Paul. Paul certainly has a lot of identity talk going on, and the markers of identity are innovative.

Cf. Baumgarten’s Flourishing of Jewish Sects in the Maccabean Era.